ATD Blog

All the Lonely People

Thu Aug 29 2019

Bookmark

Mark, a federal employee, sits at his desk surrounded by co-workers he doesn't know. For five years, he has been part of a geographically dispersed team, and the situation hasn't been easy for him. When the team split up, Mark lost the daily, in-person interactions he had become accustomed to with fellow team members. Even with the benefit of flexibility, fewer interruptions to his workflow and almost zero threat of micromanagement, the lack of face-to-face collaboration has become painful. The boredom and isolation that Mark is experiencing are so stressful that the work he used to love has been replaced by the workplace he has come to hate.

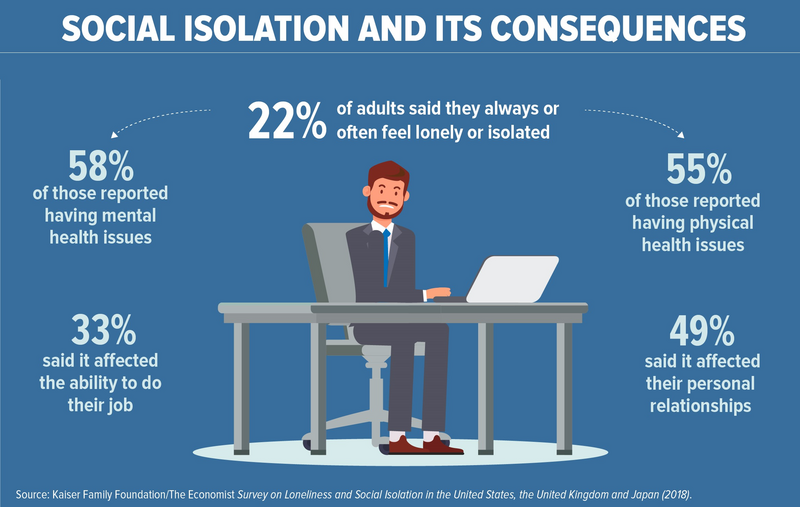

Ironically, Mark isn't alone in feeling alone. Nearly half of Americans report "sometimes" or "always" feeling alone or left out, according to a survey by Cigna Health, based on the University of California-Los Angeles Loneliness Scale. The findings, from 20,000 respondents, were clear: Loneliness is a pervasive and growing problem, particularly with Generation Z (18- to 24-year-olds) which, based on the responses, is the loneliest generation.

The research highlighted the biggest threats of loneliness: lack of sleep, reduced activity, poor eating habits and a lack of healthy relationships. And data related to loneliness in the workplace suggest that work paradoxically can both contribute to people's loneliness and also offer an antidote to it. Good relationships with co-workers can play a major role in decreasing loneliness, but the amount of time spent at work must be balanced with time off. Everyone has a different "Goldilocks zone"―the optimal number of hours spent at work―but too much or too little time on the job can significantly contribute to feelings of loneliness.

For workers who feel isolated, it may be hard to imagine that work could become a psychologically safe space where friendships easily form and flourish. To nurture an authentic culture that encourages connections and discourages exclusion, leaders would be wise to explore the causes and consequences of workplace loneliness.

Flexible by Design

One cause of workplace loneliness can be workplace design. The open office, the choice for nearly 70 percent of U.S. companies, is a good example. A recent paper, "The Impact of the 'Open' Workspace on Human Collaboration," by Harvard Business School researchers Ethan S. Bernstein and Stephen Turban, explored how architecture impacts collective behavior. Bernstein and Turban's field research showed that the modern open office architecture "tends to decrease the volume of face-to-face interaction by some 70 percent."

The study tracked two Fortune 500 multinational businesses as they transitioned to more open spaces. It found that employees in the "walled" space spent an average of 5.8 hours a day interacting face to face. In the "open space," physical collaboration time withered to 1.7 hours. Instead, employees sent 56 percent more e-mails and 67 percent more instant messages that also happened to be 75 percent longer. Bernstein and Turban concluded that hyper-stimulated open offices wind up reducing, rather than increasing, productive interaction.

Susan Cain, bestselling author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can't Stop Talking and a frequent speaker on introversion and extroversion in the workplace, notes that, "The best work spaces allow people to move freely between solo and shared spaces. Sometimes we want to work alone. Sometimes we crave company. Sometimes we want both of these things in the space of a single morning. Why not design around these natural preferences? Radically open office plans don't actually increase collaboration or decrease loneliness. On the contrary, they create giant rooms full of worker bees wearing headphones."

Cain's work with Steelcase, an office space and furniture design company, is part of her effort to educate employers about the best ways to leverage the powers of introverts. Appropriate workspaces play a big part in that effort. Cain cites a few design principles with introversion in mind, including:

Permission to be alone. This means offering workers a private, interruption-free space, the ability to remove themselves from an otherwise highly stimulating workplace.

Control over the environment. Cain's research shows that introverts are more sensitive to stimulation and have a greater need for control over their environment. They also have a lower tolerance for external forces such as noise and light.

Sensory balance. Calming influences found in organic materials help introverts manage their sensory needs.

Psychological safety. Introverts need spaces where they feel unseen―as respite from feeling perpetually noticed by their peers.

"There's a big difference between happily seeking out solo time (for getting into a flow state, or simply to recharge) vs. unhappily feeling lonely (because of social isolation or toxic interpersonal dynamics)," Cain contends. "The best workplaces maximize the former and minimize the latter."

The Social Contagion of Loneliness

A 2018 research paper, "No Employee Is an Island: Workplace Loneliness and Job Performance," found that loneliness affects job performance in several ways. Notably, loneliness has a network effect. Wharton professor Sigal Barsade determined that lonely employees are viewed as less approachable by their colleagues.

"Once a person has decided they are lonely, they become hyper-vigilant to social threat, which leads them to behave in defensive, nonsocially skilled ways and causes them to appear unapproachable and pushing people away," Barsade says. "The irony is that these lonely people who desperately want to connect are actually pushing away the very people they could connect with. And given how much work gets done through others at work, including the exchange of information and workplace help, being viewed as less approachable by work colleagues hurts the lonely employees' performance."

Managers tend to see loneliness as the employees' problem, but researchers emphasize that organizations need to pay attention. The study found that greater workplace loneliness was strongly related to poorer job performance. That's a result of lower commitment and less positive emotional attachment to the organization on the part of employees.

"Given the pernicious effects of loneliness in other life domains, and given that loneliness is domain-specific, and given the amount of time people spend at work, leaders must address the issue," Barsade says. "This is not only, of course, because it's an alienating and upsetting experience for the employee, but also because it's an organizational problem."

Production-Only Focused Cultures

The competitive nature of a highly production-focused company is one of the many examples of how work cultures can breed loneliness. On one hand, competition can be healthy. According to research published in the American Journal of Management, "The Psychology of Rivalry: A Relationally Dependent Analysis of Competition," it can increase an individual's motivation and effort to produce results. But overly competitive work environments can cause stress, secrecy, defensiveness and predatory behaviors. Too much competitiveness can also lead to feelings of isolation among co-workers and an "every person for themselves" culture.

While strategies such as cooperative sales targets and team metrics can help, the best way to encourage healthy competition and mitigate feelings of loneliness among workers is to focus on shared goals, experts say.

Humans are social creatures whose ability to come together and support one another is in large part what drove our success as a species, says Leeno Karumanchery, chief diversity officer at Mesh Diversity, a consultancy based in Moncton, New Brunswick, Canada. "Feelings of inclusion drive what we call a 'virtuous loop' that energizes us to 'do for others' in that group," he says. "In a work context, that motivates us to work harder for our teams and for our organization (i.e., longer hours, increased workload, a desire to 'make an impact'). In contrast, feelings of exclusion actually cause changes in brain functionality, leading to diminished learning capacity, poor decision-making and an elevated threat response. Simply put, inclusion helps us to be at our best for ourselves and for the people in our lives."

Balancing Technology

In his best-selling book Back to Human: How Great Leaders Create Connection in the Age of Isolation, Dan Schawbel tackles the impact of loneliness and disconnection in the workplace. The author cites more people living alone and the overuse of technology as the main culprits for an increase in loneliness. Schawbel urges people to "use technology as a bridge" to further human interaction. He advises individuals not to let technology be a barrier between them and those they need to connect with most. He also encourages leaders to take the necessary time to get to know their teams. "By solving someone's human needs, you're also solving their work needs," he says.

Schawbel's latest research, in collaboration with Virgin Pulse, is aimed at determining the best ways to enable stronger human relationships. His survey of 2,000 managers and employees across different age groups and world geographies found that offsite meetings were a helpful strategy for enabling human relationships. Schawbel learned that by gathering in environments away from work, employees were better able to escape the office talk and engage in more personal conversations. Following the offsite events, participant data showed that productivity and engagement among the group increased, while feelings of isolation and loneliness decreased.

"Really, it's about trust," Schawbel says, "because if you have never seen someone's face, you don't trust them as much. The second you meet someone, everything changes, everything."

Katie Burke, chief people officer at HubSpot, a Cambridge, Massachusetts-based marketing software company, also sees the negative impacts of technology and the role it plays in human disconnection. She believes that "workplaces need to evolve to address the fact that ultimately employees want to feel like they belong and can thrive in the workplace." She described some of the ways that HubSpot is putting resources and investment toward that goal.

One is by equipping managers with more tools to foster psychological safety in their teams. This includes formal manager training and a virtual community where managers share best practices. The company also celebrates its commitment to mental health in public and visible ways. One of its employees wrote about how therapy has made him a better manager. In the Dublin office, company leaders host events that focus specifically on mental health. All of this is an effort to normalize the language of mental health and reduce the stigma surrounding these topics in the workplace.

HubSpot also strives to build connections among employees. The company has created a monthly automated introduction to one employee so staff can easily meet someone outside of their department. The company sponsors book clubs that celebrate diversity and holds quarterly ParentSpot breakfasts that encourages new parents to connect in person. Burke notes that the company also conducts direct interventions through its employee assistance program.

"At HubSpot, one of the most important things we do to help our employees feel like they belong is to normalize moments of vulnerability. Whether you're nervous because it's your first day, anxious because of a big presentation or lonely because it's your first day back as a new parent, one of the most important things we can do is to help people realize they're not alone."

There's little doubt that loneliness, particularly in the workplace, is a growing concern. But there's plenty of proof that just by showing empathy and compassion, business leaders can create a culture of support and safety.

Copyright 2019, SHRM. This article is reprinted from https://www.shrm.org with permission from SHRM. All rights reserved.

More from ATD