ATD Blog

Better Science for Better Learning: Concept Generalization

Wed Nov 13 2019

Bookmark

Today we’ll continue the last blog post’s discussion about practice. But first, a scary story.

Stay Out of the Swamp

Some years ago, I wanted to get up to speed quickly on JavaScript, so I attended a full-day workshop. The course was cleverly designed. Under a facilitator’s guidance, I programmed a gorgeous website that included every function I needed. The next day, when I returned to work, I:

A. built a functional framework ready to show by lunchtime

B. struggled a bit but, with help from the course manual, found my way within a couple of hours

C. got stuck, gave up, and hired a programmer.

It was like a horror movie (cue trombones). I ventured into a swamp where I was cursed by a mysterious failure in behavior change.

The Curse of The One Big Project

This particular swamp is a course designed around one large-scale project. It arises when an instructional team builds a single, class-long exercise that embodies as many objectives as possible. “At the end of the workshop, each learner will have designed an entire airplane engine . . . built a complex relational database . . . planned a three-day wedding!” Each learner practices only one way to do something, in one context, with one particular set of ducks in a row. When the real world changes the activity, changes the context, or changes the ducks, the learner has no experience generalizing the lesson and falls apart on the job.

Instructional designers should be cautious about creating The One Big Project. It can be an ineffective way to teach, earning a C in information transfer and an F in behavior change. Instead, we should infuse variation into our instruction, with groups of examples and practice exercises that ask learners to generalize what they’ve learned. This way, we don’t just teach content; we also teach learners how to apply it in the messy real world. Here are two effective ways to accomplish this.

Unlock Fixed-Order Processes

If you must teach a process, carefully examine it to see whether real people do its steps in order. Yes, when you cook an omelet, you’d better break the eggs before frying them. Sometimes order is important. But here’s an example where order can get in the way.

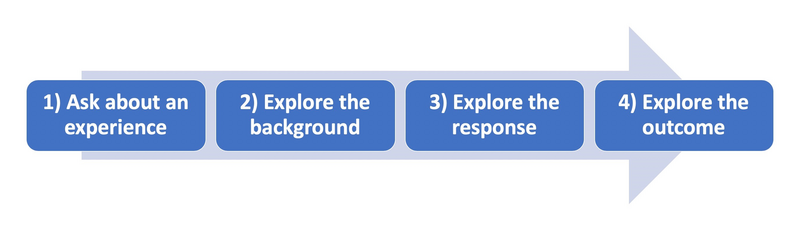

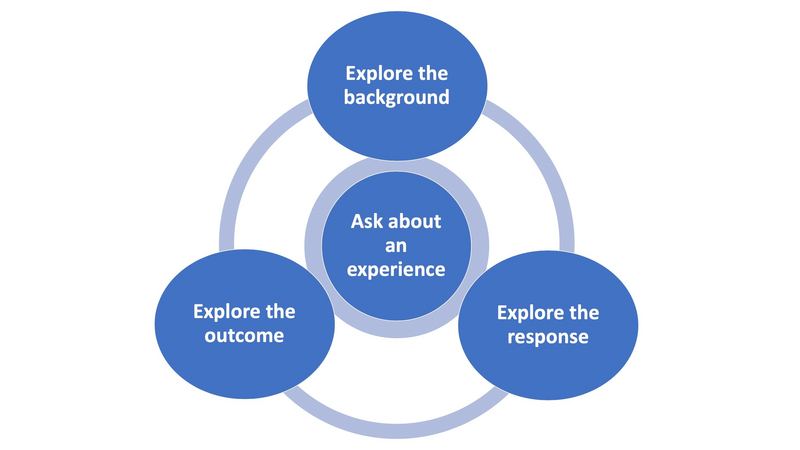

Many companies teach their managers behavioral interviewing, a method that helps identify whether applicants are suitable for job openings. It’s usually described as a four-step process: Ask about a time when a candidate did something related to the job requirements, probe the background of the situation they faced, explore how they handled it, and finally ask how things turned out. It puts four logical ducks in a row.

But if you watch managers during job interviews, you see something messier. Candidates jump a step forward or back, not knowing they’ve broken the process. Managers who’ve been rigidly trained respond by forcing the conversation back on track, or they get rattled and leave out steps, missing important clues. I even saw a manager get frustrated with the process and derail it entirely, asking his candidate, “If you were a tree, what kind would you be?” So, for behavioral interviewing, I suggest losing the numbers and re-visualizing the process.

Now the diagram teaches that after asking an experience question, managers should explore the three aspects of that experience in any order. This unlocks the interview, creating a flexible conversation, not an oral exam, while enabling the manager to gather enough information in all three areas to make a good hiring decision.

This demonstrates a great way to help learners generalize conceptual material. But learners still need practice. Fortunately, you can build flexible thinking into groups of practice exercises.

Create Exercises Set in Varied Circumstances

Don’t write one-and-done exercises. Instead, write related groups of exercises.

For classroom training, create role plays that require using a skill in at least two different situations. As part of emotional intelligence training, you may write that, “Gupta has complained that her colleague, Sandeep, is taking credit for her work. You called a meeting with them both. Do what you can to resolve this issue.” Now have facilitators run this exercise twice. The first time, facilitators secretly coach Gupta to begin shouting as soon as the exercise starts; the second time, secretly coach Gupta to be afraid of Sandeep and try not to talk.

For self-paced online training, create several different scenarios and ask, “What do you do now?” questions about each one (see Guided Practice blog post number five), making learners apply the process in different ways when facing different situations.

If you have the budget for video segments, write short scripts that illustrate more than one instance of the most important steps in a process. Show how someone skillfully handles each instance. To enhance behavior change, include a voice-over of each person’s thoughts to cognitively model decisions made under varying circumstances (see Mastery Modeling blog post number two).

In short, build coherent sets of examples that require learners to respond flexibly to a problem. Don’t rely on a procedural cookbook unless that procedure saves lives. Have learners discuss your examples; then bring each step to life with multiple practice problems. For a deeper dive into the underlying psychology, read Bowman and Zeithamova’s new pre-print, Training Typicality and Set Size Effects on Concept Generalization and Recognition.

The Only Cost Is Time

These approaches require extra conversations with SMEs to dig out variations. But when you invest the time, you can improve how smoothly your learners integrate new skills into the workplace.

Join us two weeks from now for tips on concision—how to tighten the wobbly sentence or align the wandering outline. In the meantime, let me know whether you’ve experienced The One Big Problem in your own learning. How did it go? What might have made it more effective?