ATD Blog

How We Learn and Why It’s Important

Mon Apr 15 2024

If you’re interested in teaching and learning, you’ve likely read myriad articles on ways to incorporate learning science–based principles and strategies in your training practices. Things like retrieval practice, interleaving, cognitive load, motivation, spacing, and metacognition are all relevant topics if you want to improve learning outcomes. But jumping straight to implementing techniques can leap-frog right over the foundation upon which they all sit. So, let’s step back and think about how learning happens. That is, how do we take information from our environment and turn it into usable knowledge?

The fundamentals of “how learning works” is a necessary primer to effectively implement learning science in your work. This knowledge makes us better learning designers, trainers, and educators. And, it can help us cultivate conditions that better support learning new knowledge and help learners recognize and use effective learning techniques. Perhaps most importantly, insight into how the cognitive components of learning function helps us understand how social, emotional, physical, and other factors can hinder or enhance the learning process.

Cognitive Architecture and Information Processing

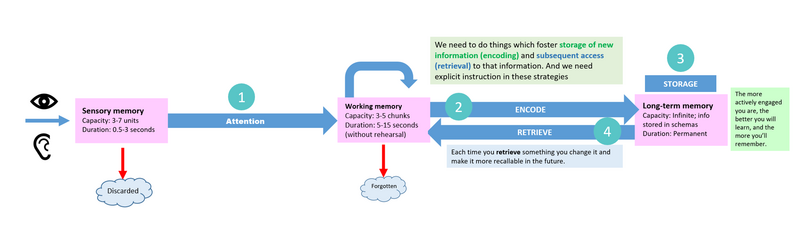

Several areas in the brain, referred to as the human cognitive architecture, are involved in learning and developing expertise. The key components of this architecture are our memory systems—including sensory memory, working memory, and long-term memory–which are at the core of receiving, processing, making meaning of, storing, and retrieving stored information. That’s learning!

Four main actions make up the flow of information within our memory systems: 1) attention, 2) encoding, 3) storage, and 4) retrieval. We call this the information processing model.

Sensory Memory and Attention

The first step in this journey begins in the environment around us. You are bombarded with stimulation coming into your sensory memory via all five senses, much of which you’re unaware of. We’ll focus here on information coming in via two main channels, audio (for example, words) and visual (for example, images). Once information enters your sensory memory, your attention system acts as a filter—directing you to only pay attention to information relevant to the task at hand. All other irrelevant data is ignored and fades away.

Working Memory and Encoding

Information we pay attention to moves into our working memory where processing can happen. But it’s not a given. Have you ever asked someone their name, heard it, and then almost immediately forgotten it? This happens because you didn’t do anything to help you remember it, or your working memory was full and there was no room to store the new name—even temporarily!

Unfortunately, our working memory is asked to do many things at once with a limited capacity. As a result, it is easily overwhelmed, and we can’t hold on to information too long without forgetting it. That’s fine for things we only need to recall for a brief time. But if we want to remember things for longer, we need to process the information. And the depth at which we do so will influence how likely we are to recall it later.

Maintenance Rehearsal

Imagine you need to remember the phone number of a friend you ran into at the train station. While searching for a pen, you repeat the number over and over in your head, hoping it will “stick” long enough. This technique is basic maintenance rehearsal, and while it works well in the short-term, the memory is fleeting. Once you write down the number and stop rehearsing, the memory is gone.

Elaborative Rehearsal

As we just discussed, refreshing information in your working memory keeps it available for immediate use. If, however, you want to store the information and use it later, you need to create a memory. You can do this by connecting the number with something you already know. Maybe part of the number was your birthday month or year, or it had some numbers in common with your house address. Consciously making connections to prior knowledge is an elaboration strategy known as elaborative rehearsal.

Making Meaning

Elaboration is primarily a strategy to improve our memory of things like facts, names, and dates. There are other strategies, including more focused kinds of elaboration, that support deeper conceptual learning. For example: organizing or categorizing information, making comparisons or analogies, using concrete examples for abstract ideas, generating explanations, and exploring how things work and why. All are ways to help transfer information from our working memory to our long-term memory for later use—called encoding. Encoding frees up valuable space in our working memory so we can learn new things. And because our long-term memory has an infinite capacity, we can keep learning new things and not risk running out of storage space!

Long-Term Memory: Use It or Lose It

With focused attention and effective use of our working memory, we make meaning of new information and embed it into our long-term memory. But that’s not the whole picture. Learning is hard work, and the final piece of the learning puzzle is practice. You might be thinking, “But if I learn something in a deep and meaningful way, shouldn’t I always know it?” Unfortunately, it’s not quite that easy. You can probably think of times when you prepared for an exam and felt confident that you knew a lot about the topic. Which you did—at the time. But if you didn’t keep accessing and using that knowledge, over time it faded.

Relevant knowledge stored in your long-term memory can be called up, or retrieved, to help you process new information, answer a question, or simply practice applying knowledge. Each time you call information to mind, you make it more recallable in the future. And if information is quickly and easily recalled, that’s a good sign that you have truly learned something. On the other hand, if you don’t practice calling it up frequently or in a meaningful way, the information becomes less and less accessible.

Summary of How Learning Works

We can understand how learning works by looking at the actions within our memory systems and how they interact to take in, process, store, and allow access to new information. For learning to happen, we must

1. Pay attention to the most relevant information coming into our sensory memory.

2. Have enough capacity in our working memory to engage with it.

3. Actively retrieve relevant prior knowledge from our long-term memory to help process new information.

4. Engage in ongoing practice retrieving information.

Understanding the fundamentals of how people learn is deeply relevant to the work of learning and development professionals. For that reason, the capabilities and the limitations of our cognitive architecture should be guiding factors for anyone looking to create effective learning experiences and environments.

You've Reached ATD Member-only Content

Become an ATD member to continue

Already a member?Sign In