ATD Blog

Snowden, Zen, and the Paradoxes of Leadership

Mon Oct 14 2013

Bookmark

I’ve been thinking about Edward Snowden, and what his story tells us about leadership—and the training and developing of leaders. Snowden, of course, has been a hot topic this summer for exposing widespread NSA surveillance on U.S. citizens, followed by his high-profile asylum-seeking. On the one hand we’re told his leaks have put lives at risk. On the other hand, the audit committee looking into NSA overreach found plenty to report.

For weeks we’ve been hearing about techno-spying on millions of innocent citizens, misrepresentation to secret courts, and an enormous, opaque, “black budget.” While Snowden has been assailed in the media for cutting and running, landing in Russia – hardly the paragon of human rights, he’s been heralded by others as a courageous whistleblower.

So, is Snowden a louse or a leader? If by “leader” we borrow Kevin Cashman’s definition of “authentic self expression that creates value,” there is little doubt that Snowden was authentically expressing himself in these actions. We could argue about whether his actions created more value than they destroyed, though. Whatever we believe today, we have to acknowledge that the perspective of history may tell a different story. Every action creates a chain reaction, and this chain has yet to fully play out.

Struggling with paradox

What Snowden was clearly wrestling with, common to leaders everywhere, was the paradox where right collides with right. It’s right to want security and, especially since 9/11, that has been a strong national concern. But it’s also right to want privacy. With leaping advances in search and surveillance technology, it’s fair to say we’ve ceded a great deal of privacy without being aware of it—and certainly without being asked.

As with all paradox, both security and privacy have value. But when one side gets increasingly funded (and increasingly powerful), the tendency is to go too far. If any good is to come from the Snowden affair, it is that we will find a healthier balance, in which our security practices and privacy standards catch up with technology.

But Snowden was also wrestling with another kind of paradox that is common to leaders everywhere: what’s right for society (or my business, organization, team) versus what’s right for me. Was Snowden motivated for the good of society? In leadership development programs, we’re often espousing the value of courage, of speaking truth to power, and standing for one’s beliefs—even when it’s difficult. Is that what he was doing? Or was he looking for personal recognition and his 15 minutes of fame? Did he start out being for the good of society, and then got frightened and had to figure out how to stay alive literally or figuratively?

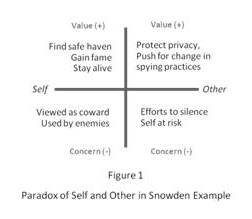

In a general sense, we can characterize this paradox as “self vs. other,” in which “other” represents the needs and interests of other people, be they members of a team or family or society as a whole. In the Snowden case, we can draw a picture of this paradox (see Figure 1).

What we know to be true of all paradoxes is that both sides have value, as well as concerns if we go too far. If we give Snowden the benefit of the doubt and say he was, at least initially, motivated by the good of others, we can identify valuable outcomes that he was perhaps hoping to bring about: protecting the privacy of citizens and being a force for change in exposing excessive spying practices.

But playing in this high stakes game, inevitably “other” forces would try to silence him or imprison him, for he surely broke a law. Not surprisingly, he would move to the other side and focus on himself, trying to find a safe haven, but also giving evidence to those who would say he was in it for himself from the beginning. Too much focus on self-protection, and he gets dismissed as a coward and used as a pawn in political brinkmanship.

Cycles of paradox

We know that paradox doesn’t solve once and for all, but its cycles can go a couple of ways. If we maintain a functional tension between the two poles, we can bring about a virtuous cycle that leads to a greater good. In this example, we could imagine a stronger society because of outspoken and strong individuals and because society supports their personal rights.

The opposite is also a possibility, where a dysfunctional tension leads to a vicious cycle of attack and counter-attack, to the detriment of both. To manage a functional tension between the two sides of any paradox calls for a dynamic balancing act that has us move between the two poles—like inhale and exhale—in service of a greater good. To get a feel for this rhythm and practice on a real paradox you’re facing, you can download this paradox mapping guide from The Zen Leader.

Paradox in leadership training

I believe paradox is of particular importance to our world of training and development, as it represents the developmental edge of leadership consciousness in most cultures. It’s a mindset we would do well to emphasize again and again.

Certainly for leaders to be successful in today’s complex, diverse, and interconnected world, they must learn how to lead when one right collides with another. Does one focus on short term or long term? Strategy or operations? Profits or purpose? To ignore one side or try to reduce the interplay of these factors to a simple compromise or point solution works only for a short time—and sometimes not at all.

The particular paradox of “self vs. other” highlighted in the Snowden case also tells a developmental tale of human consciousness, informing every stage of moral development. At a young stage, we think only of ourselves and do what we think serves us (think: “mine!”). We grow a bit older, become socialized into a family or community, and start to make some decisions in favor of others (sharing with a sibling). Grow a bit more, and we start to see that sometimes what’s good for others also is good for us (creating a harmonious family, team or society). Sometimes what’s good for us is also good for others—when authentic self-expression creates value.

As we develop, we get better at managing the paradox of self and other (or conversely one could say that managing a healthy tension between these poles is part of what fuels our development). But as the Snowden case reminds us, if we’re strong-minded individuals living amidst others having strong interests, this tension can be mighty tricky.

Zen and paradox

From a Zen perspective, this paradox leads to a still greater truth. If we engage in deep Zen training, which can take many forms but typically involves a good deal of meditation, we see this paradox as its ultimate resolution transcending self and other—indeed, all dualism.

This transcendence is not a nice thought that “I” thinks, but a dissolving of “I” altogether in a state of Samadhi. Neither is it suddenly getting absorbed into some kind of Borg-like group think, but rather losing the grip of “I,” one expands into one’s whole self. In this condition, we are our authentic, whole selves—not just a local ego, having to choose between its own interests and those of others.

In this condition, “authentic self expression” now naturally serves the whole picture. The paradox of self and other is transcended to its greatest truth: we are individual creative agents AND we are one.