ATD Blog

The Blue-Collar Drought

Tue May 28 2019

At age 13, Montez King took a machine shop class at a Baltimore high school that later landed him a job at what was formerly Teledyne Inc., earning $10 an hour. Back in 1991, that was pretty good money for a teen.

A few years later, King was earning $16 an hour as a full-time apprentice machinist, while Teledyne paid for him to attend community college two nights a week. At age 18, he had saved enough to buy his own home.

King credits that apprenticeship with giving him the opportunity to make a solid living. But he acknowledges that today, so few young adults in the U.S. are interested in so-called “blue-collar” jobs that there’s now a frightening shortage of workers who have traditionally been the economic foundation of this country—be they builders, welders, plumbers, pipe fitters, miners or mechanics.

Blue-collar jobs often pay decently. They can come with healthy benefits. Workers for these jobs are in high demand. Yet companies are finding it increasingly difficult to find people to fill these positions, which means employers are either forced to pay higher wages to secure such workers, forced to hire people from outside the U.S., or forced to move their operations overseas, where blue-collar workers are more plentiful.

“So the companies go overseas, they build overseas, and what does that do?” asks King, who is now executive director of the National Institute for Metalworking Skills. “It lowers our GDP, it lowers our ability to manufacture \[domestically\], and when we can’t manufacture, we can’t compete.”

Labor Shortage

The terms "blue-collar" and "white-collar" distinguish workers who perform manual labor from workers who perform professional jobs. Historically, blue-collar workers wore uniforms, usually blue, and worked in trade occupations.

All types of jobs have become hard to fill due to recent economic trends: The U.S. unemployment rate continues to sink, hitting a 17-year low in December (3.9 percent), and job seekers are finding work more easily than at any time since the mid-90s. Job openings in the United States have now topped roughly 6 million for five months in a row, a record streak, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The blue-collar sector seems especially hard hit. Companies are now having a more difficult time finding blue-collar workers than white-collar workers, according to a Dec. 13, 2018, report from The Conference Board, a business membership and research organization based in New York City.

A 2018 report by Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute projected that between 2018 and 2028, there could be as many as 2.4 million unfilled manufacturing jobs. That labor shortage, the report said, would have an estimated $2.5 trillion negative economic impact in the United States.

The manufacturing “industry is experiencing exciting and exponential change, as technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics, and \[the\] Internet … are rapidly changing the workplace,” the report authors wrote. “While some predicted that these new technologies would eliminate jobs, we have found the reverse—more jobs are actually being created.”

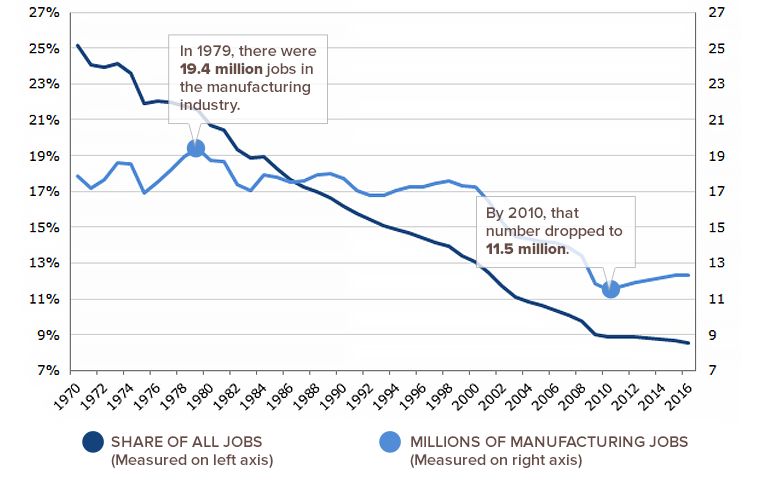

In manufacturing alone, job openings jumped significantly between October 2017 and October 2018—from 410,000 to 522,000, according to the BLS. Still, manufacturing jobs have steadily fallen as a share of employment for decades, meaning fewer and fewer people are taking manufacturing positions to earn a living. Such jobs accounted for about 25 percent of the labor force in 1970—or about 1 in 4 jobs—but less than 13 percent in 2016, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, which relied on BLS data.

Manufacturing Has Been Falling as a Share of Employment for Decades

Source: Center for Economic and Policy Research, using U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Causes

There are several reasons for this blue-collar labor shortage, say labor and economic experts, as well as those who work in blue-collar industries.

For one thing, the term “blue-collar worker" can come with a stigma, says Mason Bishop, principal at Burke, Va.-based WorkED Consulting, which provides workforce development and higher education consulting. In fact, people like Bishop no longer find the term acceptable. He insists “gray-collar worker" or “technical careerist" is more appropriate these days.

For another thing, an increasing number of high-school graduates are choosing to get a four-year college degree, often at the urging of their parents, experts say.

Fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions increased 23 percent between 1995 and 2005, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Between 2005 and 2015, enrollment in these same institutions increased 14 percent, from 17.5 million to 20 million.

“Younger workers are reluctant to take on these \[blue-collar\] positions because … parents perceive these jobs as requiring a lot of manual hard work, which for certain positions that have become more high-tech, is no longer true,” says Aparna Mathur, resident scholar in economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “The image of these jobs as being hard and ‘dirty’ often discourages people from applying.”

That's the case even though a college degree no longer guarantees a professional, secure or well-paying job, King says.

“Everyone is sending their kid down the same tunnel, but when they get out of college, there are thousands of them competing for a few \[professional\] jobs,” he says. Often, they come out of school with high debt and initially find only low-paying jobs.

Katie Bardaro is lead economist and vice president of data analytics at PayScale, which provides compensation data on jobs. She says it’s no longer the case that a college degree will lead to a well-paying job with good career growth opportunities.

“A number of people are likely making the wrong choice of attending a traditional four-year school versus a trade school program,” she says. “We encourage students to research the potential earnings for their programs of choice to ensure they are making a good bet.”

To support this, PayScale annually examines the earnings potential of hundreds of major programs for associate- and bachelor's-level educations.

Young adults also may not realize how much money they can earn in blue-collar jobs.

“If you took one of these jobs we prepare you for, which requires more than a high school diploma, but less than a college degree, more than 50 percent of those jobs will pay more than the jobs that require four-year \[college\] degrees,” King says.

Michael D’Ambrose can confirm this. He is senior vice president and CHRO for Archer Daniels Midland Co., a Chicago-based global food-processing and commodities trading corporation. At his company, he says, “we pay about 50 percent more for a five-year apprentice technician than we do for an electrical engineer who just graduated” from college.

Skills Training Declines in the United States

Despite the money that, say, an elevator mechanic can earn with 10 years of experience—that would be a median income of $88,200—many of these jobs still don’t pay enough to lure young adults, says Peter Cappelli, a professor of management at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. He believes companies would rather hire foreign immigrants or move their operations overseas, where people with blue-collar skills are often more plentiful, than pay higher wages for those same people in the United States.

“If you pay people enough, they will do these jobs,” he says. “But wages remain flat. In addition to the pay, schedules have become more challenging for employees, with more required overtime, and job security has largely evaporated.”

Moreover, companies tend to demand that their blue-collar workers already have several years of experience to land a job, Cappelli says, but many aren’t willing to invest in programs that give young adults those very skills.

“We cut back on vocational education programs starting a generation ago, in the belief that those programs tracked students into dead-end jobs,” he says. “Today, employers want people who already have the skills that, in the past, they would have gotten through \[that type of\] training. Everyone wants someone with five years’ experience, but no one wants to provide that experience. Union apprentice programs have dried up, and the only real place to get those skills now is at community colleges. Welding, for example, is typically a two-year program in community colleges.”

This is not the case in other developed countries, King says. Those who have completed skilled-trade apprenticeships represent about three-tenths of 1 percent of the entire U.S. workforce, he said. In some countries overseas, he said, they represent more than 30 percent of the workforce.

“So overseas, countries are promoting and capitalizing on skills training, while we \[in the U.S.\] started promoting college degrees. That’s what we put in front of our kids every day. That’s what they see on TV. Overseas they said, ‘Hey we’re going to gain on the U.S. by teaching manufacturing.’ They start \[kids\] off young: In the sixth, seventh, eigth grades, kids are coming out early with these skills. So \[overseas\] companies focused on that, and look what happened with car \[manufacturing\]. In the '80s and '90s, we got our butts whipped because we dropped the ball.”

Partnering to Close the Skills Gap

There are a handful of U.S. high schools that are investing significantly in trade-skills training.

In Janesville, Wis., schools are giving kids critical-thinking and specialized skills to help them meet local business needs.

"We're trying to shift what learning looks like—away from traditional education where students listen to a teacher deliver content and then repeat that content on a test," says Janesville schools superintendent Steve Pophal. "We don't feel that type of education really prepares kids for the future world that they're going to be walking into."

Pophal is also sending teachers back to school for master’s degrees at the local Blackhawk Technical College so they can teach specialized classes that earn students college credit. Some of the city’s high schools are creating programs in mechatronics, a growing field that combines mechanical engineering and electronics.

“Businesses are certainly responding to the labor need,” Mathur says. “One way is with paid apprenticeship programs. Employers are reaching out to high schools and community colleges to recruit students for one-to-two-year, on-the-job training programs. These are paid positions and teach workers exactly the skills that the company needs for them to fill vacancies.”

For instance, she pointed to one program called Wisconsin Fast Forward, which awards grants to state technical colleges to train high school students for high-demand, blue-collar fields.

“I think employers recognize that there is a need, not just to address the skills gap but also the image gap,” she says. “So they are trying to reach students as early in their schooling as possible to expose them to these jobs, to give them tours of their factories and to provide them opportunities to learn about the industry.”

King’s company partners with Haas Automation—an Oxnard, Calif.-based company that builds machine tools and has a $140 million endowment for scholarships designed to change perceptions about blue-collar work and to inspire interest in such jobs.

“What we help \[promote\] is the work-and-learn model,” he says. “Why do you have to make this tough decision of going to college or getting \[trade\] skills and working right away? Why not go to college, while also getting real experience at the same time? The statistics \[show\] that under this model, kids earn their degrees faster than the kids who just go straight to college.”

Help From the White House

Still, there aren’t enough of these programs, D’Ambrose says.

“I’d love to hear about more,” he said. “The concept of vocational \[classes\] was very apparent when I was in high school, but today it’s not. I have two boys, and when they were in high school, there wasn’t a curriculum or a way for them to think about ‘What if I want to be a police officer?’ Community colleges were established to be a link between school and work, and they were supposed to focus on meeting the workforce needs of local communities. For lots of reasons, they’ve become four-year \[college\] institutions.”

D’Ambrose’s company—as well as the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM)—is involved in apprenticeship and skilled-trade training programs to ensure that companies have the bodies to fill future labor needs.

One of those training programs is called Jobs for America’s Graduates. Participanting employers such as Archer Daniels Midland visit high schools and talk to students about “the many opportunities we have that may not require college,” D’Ambrose said.

In July 2018, President Donald Trump, responding to companies’ struggles with a shortage of skilled workers, signed an executive order designed to better align government training programs with industry demands.

The order creates a Council for the American Worker, led by the secretaries of commerce and labor, that will consolidate federal programs and fund new job-training initiatives, in part by expanding apprenticeship programs and retraining older workers without college degrees.

As part of the effort, companies and trade unions have committed to funding nearly 4 million slots for apprenticeships, retraining workers and offering continuing education programs over the next five years. SHRM has joined this White House initiative to expand workforce training by committing to educate and prepare more than 127,000 HR professionals through the SHRM-CP and SHRM-SCP certification programs.

The Struggle Ahead

Businesses continue to struggle to recruit people to fill blue-collar jobs, especially as older workers in these occupations retire, experts say.

If companies can’t find the labor they need, experts said, the alternatives are to hire outside contractors at high costs, hire immigrants, or move operations overseas.

Bardaro believes that market demand will eventually lead to higher wages for blue-collar jobs, as well as an increase in reliance on automation.

While there’s a perception among young adults that many blue-collar jobs are being replaced by robotics, blue-collar industries still need workers to make sure those robots are designed, built, maintained and run efficiently.

Every two years, the Association for Manufacturing Technology coordinates the International Manufacturing Technology show. What the association reported at one recent show, King said, was that for every job that technology replaces, five more are created.

“If a robot takes the place of a laborer, that robot has to be programmed, maintained, designed,” King says. “You can’t just buy a robot and put it on the floor; you have all those jobs required to keep it running.”

And there are many blue-collar jobs that aren’t at risk of being replaced by robots anytime soon, Bardaro says. Many roles require expertise, human interaction and problem-solving skills in areas such as plumbing, woodworking, carpentry, welding and appliance repair.

“These fields not only offer a number of open opportunities, but good career growth and earnings—the things a college degree can no longer guarantee,” she says.

Copyright 2019, SHRM. This article is reprinted from www.shrm.org with permission from SHRM. All rights reserved.

You've Reached ATD Member-only Content

Become an ATD member to continue

Already a member?Sign In