ATD Blog

The Dual Coding Advantage: Retain and Process Information More Effectively and Efficiently

Factors you should keep in mind regarding dual coding when designing learning experiences.

Mon Aug 05 2024

Much of what we learn comes into our brain as language (either written or spoken words). Until we have done the meaningful processing necessary for us to encode things into our long-term memory, it is pretty difficult for us to retain much of this new information before it is dumped out. Or forgotten. But what if there was something we could do to help increase our ability to retain and process new information and even allow us to connect it to our prior knowledge?

Let’s explore this idea with a group activity I often do in my learning science workshops. Participants see 14 pairs of words projected on a screen in succession for five seconds each. The word pairs contain a stimulus word and a response word. For example: cause - meaning; sofa - bicycle; judgment - concern; museum - antelope; truck - apple; purpose - value.

The participants’ objective is to try and remember the word pairs so that later, when I show them the stimulus word, they will remember the associated response word. They can use whatever techniques they can think of to help them remember the word pairs.

When you read the example word pairs above, did anything strike you about them? You may notice that some of the word pairs, for example, “museum - antelope,” are more easily visualized than more abstract word pairs, such as “judgment - concern.” That is, of course, if you know what a museum and an antelope are. If you don’t, then you won’t be able to visualize them. It turns out that in a memory test, people typically remember more words in the “easily visualized” group than the abstract group. This is because when we form mental pictures of objects, words, or ideas, we remember them better. Why? Let’s go back to how we process information coming into our brain.

Processing Information

Our mind processes information coming in from the environment via two parallel channels, verbal (like words—in spoken or written form) and visual or nonverbal (for example, images). When we combine information from both channels, we create two pathways for remembering the same information later on instead of one. Doing so also affects the potential for cognitive overload. Because the information is coming in on parallel tracks, we can maximize our working memory capacity. Beware though, either channel can become overloaded, so we still need to be mindful to avoid overwhelming learners with too much information in either format.

Learning experiences that represent material in both words and pictures encourage learners to make connections between the different representations of the information. This helps make the experience more meaningful and more likely to be committed to long-term memory, or help you solve a problem. By contrast, providing words alone may encourage learners—especially those with less expertise—to engage in more shallow processing, or to become overwhelmed.

Let’s look at another example.

Suppose someone asked you the following question:

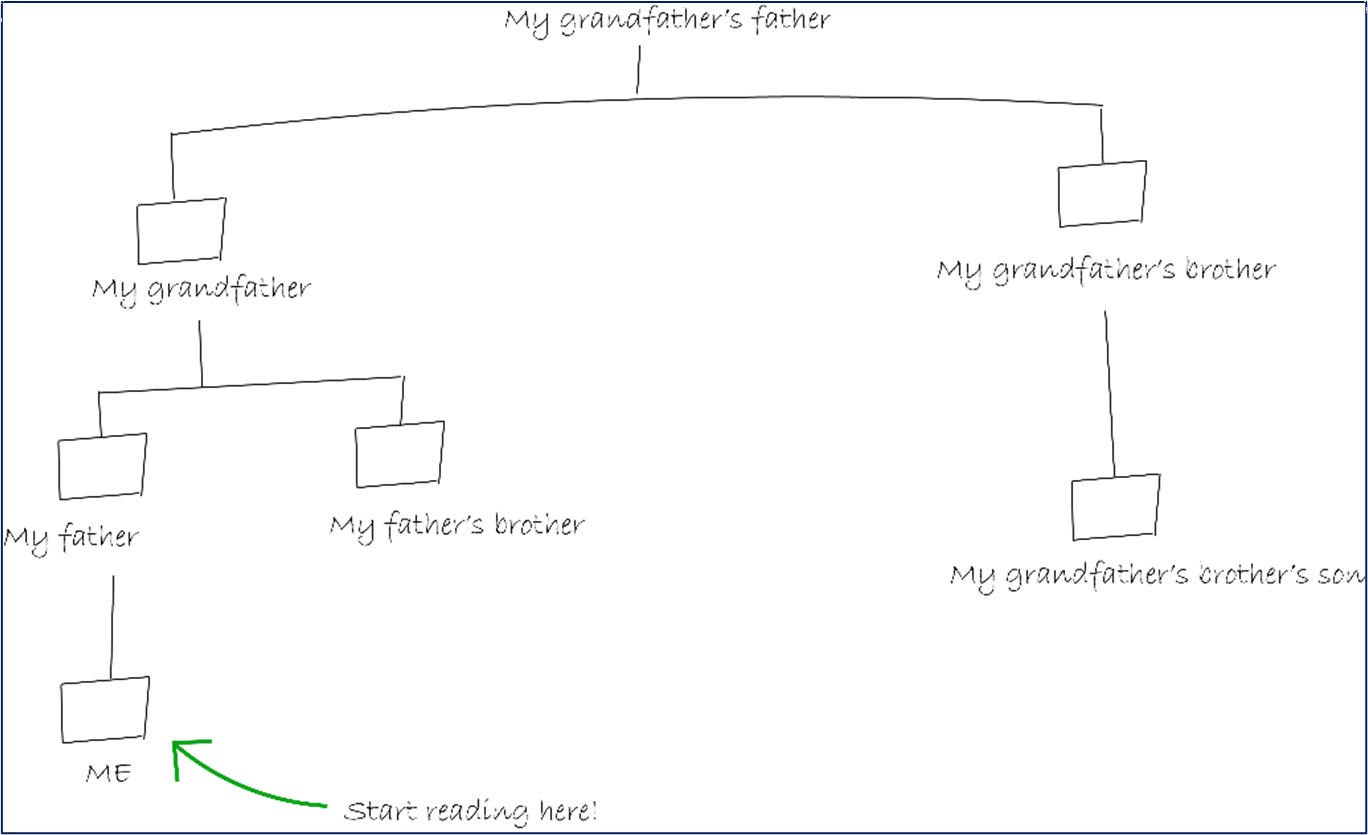

Which of the following statements is true?

My father’s brother’s grandfather is my grandfather’s brother’s son.

My father’s brother’s grandfather is my grandfather’s brother’s father.

At first glance, both statements are quite complicated to understand. What if the problem also included this diagram—does that help?

Applying the principle of dual coding by adding a visual that represents the elements in the statements does a few things:

Makes the situation less abstract, and more concrete

Offloads some of the mental processing to the visual channel

Frees up some of our mental capacity so we can answer the question

Once we have the picture, we no longer need to try and keep the complicated hierarchy of relationships in our working memory. We have offloaded that aspect to the visual and now can use it to help us figure out if either of the two statements are true (in case you’re wondering, “A” is not true, but “B” is!).

Strategies for Using Dual Coding

Things to keep in mind regarding dual coding when designing learning experiences:

The image and the verbal information should focus on the same thing and not try and add or teach additional information. As we saw in the “grandfather’s father” example above, the visual represents what is in the text in a more accessible format and the words describe what is in the visual. Taken together, they help support our ability to solve the problem without getting overloaded.

Include images that are meaningful and contribute to the learning experience in some way. If visuals are not relevant to the topics being learned (purely decorative, for example), they will distract from, rather than enhance learning.

Don’t present the same exact information in spoken and written words. For example, reading aloud written text on a slide. Contrary to what you may think, this is not an example of dual coding—even though the information is being presented in “two ways,” they are both verbal. Because your working memory must process the same information twice, it can quickly become overloaded. Verbal information should come either in spoken OR written form, but not both at the same time.

Remember, we can only hold a certain amount of information in our working memory before it gets overloaded. As with any learning experience, if too much information is presented at once (even if it includes words and images), too quickly, or in ways that distract learners from processing information in a meaningful way, learning will suffer.

You may be thinking that I am advocating for the benefits of certain “learning styles.” But no! Dual coding predicts that everyone should benefit from an increase in working memory capacity if visual information is paired with verbal information in ways that support, augment, and enrich learning.

Summary of Dual Coding and Learning

Information comes into our brains via two main parallel channels: verbal and visual or nonverbal.

Forming mental pictures of objects, words, or ideas helps us remember them better.

Using both channels, working memory’s capacity is maximized because we have two pathways for remembering the same information later on instead of one. We also reduce the potential for cognitive overload.

Dual coding is most effective when visuals are relevant to the learning content. Overloading either or both channels can hinder learning rather than enhance it.