ATD Blog

What Do You Know: Why Do People Forget What They Learn?

Wed Sep 28 2016

Bookmark

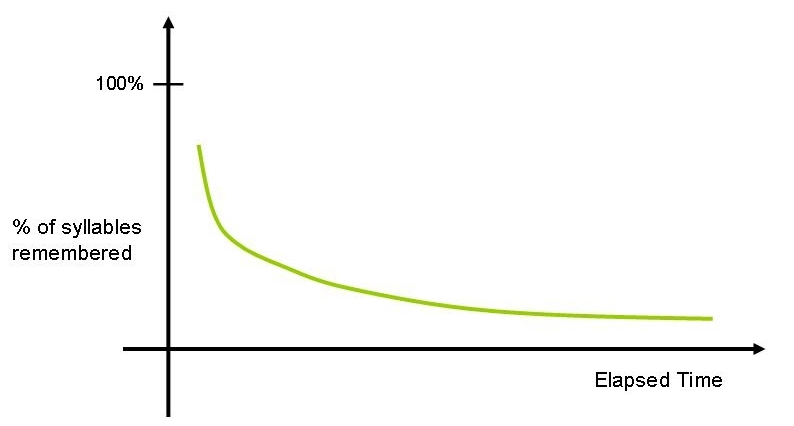

There are widespread ideas in organizational learning about how people forget at a specific rate, depending on how they learned the information. You may have seen something like this: We remember 10 percent of what we read, 20 percent of what we hear, 30 percent of what we see and hear, and so on. And you may have seen references to Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve, which describes the nature of forgetting as exponential (Figure 1). He plotted forgetting on a graph and showed that without reinforcement, forgetting happens very rapidly. The green line in Figure 1 shows the rate of forgetting with no reinforcement.

Figure 1. Ebbinghaus’s Forgetting Curve

Source: https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/File:Ebbinghaus\_Forgetting\_Curve.jpg

Do these ideas about forgetting correctly represent what we know about forgetting? This is an important concept because what we know about forgetting should influence how we train for remembering.

Read the question below and select what you think is the best answer. Then we’ll discuss what recent research tells us.

**Does forgetting primarily depend on how the information is presented and how long it has been since the information was presented?

**

A. Yes, forgetting depends on how the information is presented and how long it has been since the information was presented.

B. No, forgetting depends only on how the information is presented.

C. No, forgetting depends only on how long it has been since the information was presented.

D. No, forgetting depends on how the information was learned.

Here’s one thing you can remember: If anyone lists specific percentages about how people forget, those percentages are made up! People do not remember, as a rule, 10 percent of what they read, 20 percent of what they hear, and so on. If something seems preposterous, it probably is!

Now let’s take on Ebbinghaus’s famous forgetting curve, which was pretty nifty educational research for his day. In 1885, Hermann Ebbinghaus memorized nonsense syllables and then plotted his ability to remember them over time on a graph that we now know as the famous "forgetting curve." Today, we would ask a couple of questions about this research:

Is a quantitative study (a study in which something is measured) with one person (an N of 1) adequate? We typically want a larger number of subjects.

Is forgetting nonsense syllables the same as forgetting things that have inherent meaning? No, they aren’t the same.

So while Ebbinghaus can be considered the initial memory researcher, we have learned a lot since then. The answer to the quiz is D. Answer C has merit as well (if the word only was removed), as we are about to find out. That is why we need to train close to the time it will be needed.

Why People Forget

The science of learning is nuanced and forgetting is no different. Many people think we “record” what we see and hear, but that’s not accurate.

Perhaps one of the main reasons for forgetting is that we never remembered in the first place. To forget something, it must first be remembered (encoded in long-term memory). That means it must be perceived, paid attention to, processed in working memory, and finally encoded in long-term memory.

I’ll talk about what we can do to make that process more likely in the future. The rest of this article assumes that remembering has occurred and there is something to forget.

A 2016 article in the journal Psychological Science by Talya Sadeh and colleagues features a discussion in memory science about why we forget, with implications for learning and development practice. The two reasons that memory scientists believe we forget include decay or interference. Decay means memories fade over time if they have not been accessed enough. Interference means memories become less accessible as similar information is acquired.

Sadeh and colleagues found that the type of forgetting that occurs depends heavily on how the initial memory was created. According to the memory scientists, declarative memory (things we can state that we remember, known as explicit memory) takes one of two forms: familiarity or recollection.

Familiarity includes memory and judgments without a lot of detail. For example, I am familiar with mortgages and have some opinions about what is best. But I really don’t know a lot about them other than my own experiences. If a mortgage expert asked me targeted questions, she would see that my knowledge is shallow and limited. Familiarity-based memory tends to breed Facebook fights.

Recollection memory recovers specific details in their context. When recollecting details about baking at high altitude versus baking at lower altitudes, I can discuss what works fine at lower altitudes but fails at higher altitudes. Cookies, for example, tend to flatten much more quickly at higher altitude. When this happens, you end up with one giant, flat (but still delicious) mega-cookie. One way to get around this is to bake cookies at higher temperature for less time.

Familiarity and recollection memories are stored differently in the brain. Can you guess whether familiarity or recollection is more resistant to interference? If you said recollection, you are correct. But although recollection memory is more resistant to interference, it is less resistant to decay.

What are some implications for designing instruction and performance?

Interference:

Anything that isn’t learned deeply, such as something learned with the ability to be directly applied in the work context, is likely to be forgotten easily.

If you are going to design for easy forgetting, provide information resources for people to reference later.

Decay:

Designing for application on the job means you must know people’s jobs.

Things learned deeply are subject to decay.

Cognitive science shows us how to resist decay: through regular use and recall.

There are many ways to add regular recall and use to resist decay. Can you think of some?

How we train can greatly influence how much people remember (the other end of the forgetting equation), and I will discuss methods that help people remember soon.

References

Ebbinghaus, H. 1885. Über das Gedächtnis. Leipzig: Dunker.

Murre, J.M.J., and J. Dros. 2015. “Replication and Analysis of Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve.” PLoS ONE 10(7): e0120644.

Sadeh, T., J.D. Ozubko, G. Winocur, and M. Moscovitch. 2014. “How We Forget May Depend on How We Remember.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 18(1): 26-36.

Sadeh, T., J.D. Ozubko, G. Winocur, and M. Moscovitch. 2016. “Forgetting Patterns Differentiate Between Two Forms of Memory Representation.” Psychological Science 27(6): 810-820.