TD Magazine Article

Global Leadership Begins With Learning Professionals

With all of the volatility and uncertainty happening in the world and in the workforce, our profession must take responsibility for creating effective global leaders—starting with ourselves.

Mon May 07 2012

Our world is increasingly volatile, uncertain, and complex. This changing context is discussed at length in books by Bob Johansen (Leaders Make the Future), Adrian Done (Global Trends), and others. Population growth, urbanization, and the increasingly diverse mixture of old and young workers will continue to transform the global workforce. In The 2020 Workplace, Jeanne Meister and Karie Willyerd describe additional forces that are shaping the workplace—including mobile technology and social learning.

People around the world are now bound together by our interconnectedness as well as economic uncertainty. People everywhere are asking what it takes to be an effective global leader. In the past, they tended to look to the United States for guidance. Those days are gone, although U.S.-based corporations and consulting firms still have disproportionate influence through the competency models they promulgate. Many of those models are under siege, particularly those that idealize a particular type of leader.

For example, six leadership styles (performance oriented, team oriented, participative, humane, autonomous, and self-protective) were ranked differently by various cultures in the epic Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) Study. That study found 22 universally desirable leader characteristics—such as trustworthy, encouraging, decisive, and communicative—plus eight that were universally undesirable—for example, asocial, noncooperative, egocentric, and dictatorial. It also found 35 traits that were culturally contingent, including enthusiastic, logical, micromanager, and risk taker.

With all the shifts happening in the world and in our workforce, we need new types of global leaders to help organizations navigate complexity and change. Those of us who are managing learning functions must help leaders perform tasks that are required today, yet equip people to cope with ambiguity and perform what will be needed tomorrow. We need to collaborate with other disciplines to create leadership models and training tools that will equip global leaders to master new challenges. We also need to step up as global leaders ourselves.

Unfortunately, many learning professionals do not see themselves as leaders, much less as global leaders. In our article on global leadership in the June 2012 issue of the Industrial Organizational Psychologist, we argue that four shifts are required for everyone:

1. cultivating the "being" dimension of human experience

2. developing multicultural effectiveness

3. appreciating individual uniqueness in the context of cultural differences

4. becoming adept at managing paradoxes.

If we can help ourselves and other leaders become adept in these areas, we can shape how global leadership is practiced in our organizations.

Cultivating "being"

"Doing" is what we do, while "being" is who we are. Being is our energetic presence. It can be experienced by others as the atmosphere we create. Interculturalists estimate that as much as 93 percent of message interpretation relies on nonverbal channels. Cultivating the being dimension of human experience requires getting in touch with our identity as well as our energetic presence, and then behaving in more congruent and authentic ways.

Barbara Schaetti, Sheila Ramsey, and Gordon Watanabe developed six practices as part of their personal leadership methodology (attending to judgment, attending to emotion, attending to physical sensation, cultivating stillness, engaging ambiguity, and aligning with vision) that can help people to develop in this area. Adair Nagata's work on bodymindfulness also is relevant. She stresses the importance of heightening our bodily awareness and the congruence of our body language when communicating with people across cultures. Joshua Ehrlich's work on reflection and "mind-shifting" is another vehicle for building capabilities in this area.

One of our corporate clients recognized long ago that being authentic was a core capability for the leadership it wanted to cultivate. It commissioned coaching for all global leaders to heighten everyone's authenticity in conjunction with accelerating their leadership performance. Part of that effort involved everyone identifying their own purpose—and figuring out how their personal purpose could flourish in alignment with the company's purpose. "Walking their talk" as leaders became more personally meaningful.

As learning professionals, we need to look at our own being, what is conveyed by our own presence and energy. We must use our own energetic presence to convey richer messages inside and outside of our classrooms—as well as promote the notion of being in our organizations. This involves helping all employees to pay attention to who they are and equip them to be who they want to become. In fact, helping our leaders cultivate their being dimension may have the greatest ROI in terms of increasing their overall effectiveness.

Developing multicultural effectiveness

Both of us experienced living and working in another country for more than six years. We are luckier than most to have had that experience. Our worldviews were changed forever, along with the way we relate to people from other cultures. However, people don't need a relocation experience to develop multicultural effectiveness. There are plenty of opportunities in daily life much closer to home.

While there is no consensus about what intercultural effectiveness means, it undoubtedly involves the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations, along with adapting one's behavior to each cultural context. We also believe it involves appreciating differences and being humble about what we do not know.

We were surprised to see that fewer than 10 percent of the corporate competency models that we examined during the past year contained any language related to global work or intercultural effectiveness. That reminds us of the old saying that if you can't measure it, you cannot manage or improve it. Luckily there are assessment tools such as the Global Competencies Inventory (from the Kozai Group) and the Global Mindset Inventory (from Thunderbird University) that can help with the measurement.

It is vital for learning professionals to develop greater multicultural effectiveness as well as help leaders in this arena. We must become more aware of our own cultural values and how those play out in various learning activities. We also need to recognize that our assumptions about how people learn and perform—and why—may be culturally biased. It would help to involve a cross-cultural team in designing the talent management system and all learning activities. If that's not possible, engage someone with an external perspective to challenge your assumptions and help raise your awareness.

Understanding our own ignorance and limitations in working with other cultural groups may help us to adopt an attitude of humility and respect as learning professionals, particularly when conducting training. In the future, we will see more people from different cultures who have a different frame of reference than our own participating in our training programs. We must avoid being U.S.-centric (for example, thinking people should learn from us) while enabling people to learn from one another and from wisdom traditions in other cultures.

Appreciating individual uniqueness

Many people learned about cultural differences by being exposed to the bipolar cultural dimensions developed by Geert Hofstede and others (for example, power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, and long-term orientation). It is well-documented that national cultures differ on these dimensions. For example, the United States is high on individualism and low on long-term orientation. Japan is high on both masculinity and uncertainty avoidance, and lower on individualism.

"Sophisticated stereotypes" such as these can help us understand and appreciate cultural differences. However, they can become dangerous if they turn into negative stereotypes. Leaders must pay attention to the uniqueness of each individual to understand and take advantage of her motivation. We need to adopt a holistic perspective that focuses on someone completely, not just his job or country of origin. We must try to understand each person's unique strengths as well as her multilayered cultural identities.

Many learning professionals will have an opportunity to take a courageous personal stand in this area. Depending on the extent of cultural stereotyping already in place, we may need to confront those stereotypes and propose new initiatives for developing global leaders. Meanwhile, it will be important to appreciate unique contributions from everyone on the training and development team, including stakeholders and suppliers. We should avoid using talent management and training systems to categorize people excessively—and ensure there is room to identify and develop individual uniqueness as well.

Managing paradoxes

Paradoxes are ubiquitous in modern life. According to an article in Academy of Management Review, Wendy Smith and Marianne Lewis describe paradoxes as "contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time." Marty Gannon defines paradoxes as "a statement, or set of related statements, containing interrelated elements opposed to one another or in tension with one another or inconsistent with one another or contradictory to one another (i.e., either/or), thus seemingly rendering the paradox untrue when in fact it is true (both/and)."

We identified 10 paradoxes facing global leaders:

Strategic and operational—Global leaders should operate from a long-term perspective when pursuing strategic opportunities and must ensure that all the day-to-day operations are planned and managed.

Taking charge and empowering—Global leaders need to exercise control over groups of people and engage and empower employees to execute what needs to be done.

Results and relationships—Global leaders must focus on achieving organizational goals and bottom-line results, and should build relationships with myriad stakeholders to create alignment and foster collaboration.

Listening and expressing—Global leaders should ask questions and listen to a variety of perspectives, but also must clearly express their own point of view.

Global and local—Global leaders need to operate with a global, cosmopolitan mindset and be sensitive to local markets.

Common group and uniqueness—Global leaders should pay close attention to common group characteristics and respect cultural differences, but also must appreciate the unique qualities of each individual.

Open mind and decisiveness—Global leaders have to be open to others' ideas with a nonjudgmental attitude, but must analyze data and make decisions, often without consulting others.

Consistency and versatility—Global leaders must provide clear and consistent direction to others, but also adapt to particular conditions, situations, or people.

Humility and confidence—Global leaders need to be humble about their own accomplishments, limitations, and mistakes, but also should convey self-confidence that attracts others to trust their leadership.

Doing and being—Global leaders should consider what they do and make things happen. At the same time, they must be mindful of their energetic presence.

Those paradoxes are not all unique or necessarily global in scope. In fact, learning professionals everywhere are facing most of them as well (particularly results and relationships, and listening and expressing), although the corresponding behaviors may be different.

For example, our version of the strategic or operational paradox may involve thinking about future-oriented, strategic issues while managing our LMS. Our version of the global or local paradox may involve promoting corporate training standards while honoring and respecting local customs.

Our profession must face gnarly paradoxes head-on rather than shy away from the difficulties or ambiguity they represent. We can start by monitoring our own tendency to engage in either/or thinking rather than expressing a both/and perspective.

We should try to understand what paradoxes play important roles in our own cultures and organizations—and then find ways to strengthen people's paradoxical mindset and capabilities to deal with them. Author Barry Johnson's polarity mapping approach can be a good tool for doing this work with individuals and groups.

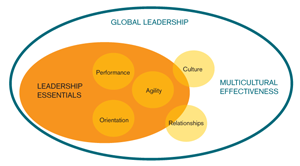

The diagram below shows the relationship between global leadership and some of its components such as multicultural effectiveness and handling paradoxes. However, global leadership always is more than the sum of its parts thanks to the complex, contextual nature of human performance—where one's effectiveness in a particular culture is determined by many things, including whether the culture is high- or low-context itself.

Embodying the shifts

We have opportunities to develop better global leaders in every area of expertise (see sidebars). For example, those of us who design learning can structure activities that will help learners use all their senses (mental, emotional, and physical) to collect input and integrate across multiple contexts. Those of us who deliver training can anticipate and prepare for challenges involved in training people who are using English as a second (or third) language, who may not comprehend all the content.

Although it may be time consuming or impractical for us to learn a second language, we can check for comprehension and arrange for participants to discuss course content in their local languages. The Essential Guide to Training Global Audiences by Renie McClay and LuAnn Irwin is a useful resource. Coaches can explore what multicultural muscle needs to be developed—such as curiosity or positive mindset toward difference—and then work with their clients on developing that capability.

Meanwhile, people working in career planning and talent management could do more to acknowledge paradoxes facing leaders. One such paradox occurs in succession-planning situations, where people may be encouraged to share their best talent with the larger organization, yet want to keep that talent in their own area. People involved in facilitating organizational change should stress the importance of being for change sponsors and champions—because people who are affected by change will watch the leaders' behavior, not just hear or read their words.

Those of us who work on improving human performance may need to adapt standards developed for a Western performance context to reflect alternative ways to accomplish the same task in other cultures. While managing organizational knowledge, we could analyze practices for capturing and storing organizational knowledge; if everything is in English, that might limit contributions and use by other cultures. While measuring and evaluating, we should recognize that most assessment systems depend on observable behavior or results rather than things like being—and that competency models may not capture individual uniqueness effectively.

The world has a desperate need for better global leaders to navigate all the complex and ambiguous challenges that lie ahead. Our profession must take responsibility for creating better global leaders in our organizations—starting with developing ourselves as global leaders.

You've Reached ATD Member-only Content

Become an ATD member to continue

Already a member?Sign In