TD Magazine Article

Let’s Make a Deal

Improve your negotiation skills.

Tue Oct 01 2024

Bookmark

TD leaders constantly face tug-of-war negotiation scenarios with stakeholders over resources, staff workloads, project scope, and deadlines. To be effective, you must balance various parties' needs while advancing your own objectives. That involves understanding stakeholder motivations, setting clear goals, strategizing approaches, and managing outcomes. With strong negotiation abilities, you can foster collaborative relationships, align expectations, and position your team for significant growth and success.

Understand stakeholder needs

When negotiating, it's important to know the key objectives of stakeholders and the priorities they assign to the objectives. Identifying stakeholders' burning issues enables you to create negotiation plans to deal with the most pressing ones and avoid wasting time and energy addressing less important matters.

To determine someone's key objectives, ask what their priorities are and why. Pose either-or questions (for example, "Would you prefer this or that?") and use takeaway tactics (for instance, "I can't give you that, but I can offer you this."). Note the nuance in those two statements. In the former, you are extending the perception of control to the individual. In the latter, the perception of control remains with you.

While it is a subtle point, the perception of control can make some people comfortable moving forward. With others, control may feel like a burden. You must know with whom to extend control or not; it conveys power.

One way to test the degree of control that someone will accept is to observe their body language when you make a request. Someone displaying signs of uneasiness (such as moving away or noticeably shifting their body) may indicate that you have passed their threshold. When you witness such reactions, probe further by softening or hardening your request based on what you seek to achieve. Then, observe their body language to assess the effects. If they exhibit the same actions, that may confirm the person's willingness to reject the extension of control. By contrast, someone displaying positive body language (such as leaning in, smiling, or becoming noticeably excited) demonstrates that they welcome the extension of control.

In all cases, be mindful of the nonverbal reactions to your queries. Subjects of those queries will return invaluable information about their inner thoughts—some of which they may never speak aloud. Someone's inner thoughts will validate their key objectives.

Thus, to benefit more broadly from the perception of control, learn how to use it and its proper timing deployment. Doing so will help you test, validate, and gain insight into someone's key objectives and priorities.

Establish your objectives

Now that you've pinpointed the stakeholders' goals and objectives, you must define your own negotiation goals. To achieve the outcome you seek, think about the resources you may need, what it may take to get stakeholders on board, who may oppose your efforts, and where leverage may lie.

Always examine how you obtain and use leverage in any negotiation because it can be the source that transforms your position from a loss to a win. To highlight the point of leverage, determining who may oppose you, and how to get stakeholders on your side, consider a two-phase negotiation scenario for a time-sensitive project. The first phase involves securing staffing resources; the second phase entails implementing the project's objectives.

Phase 1. A TD leader, Christelle, makes a request to stakeholders for an additional two, five, or seven staff members. She knows she can get the project up and running and completed on time with five people, while seven would ensure Christelle can address additional requests in phase 2 without an undue burden on the project's timeline.

If, however, opposing forces wish to allocate only two people, Christelle can highlight how that would create stress lines throughout the project's implementation phase and cause the TD team to not deliver it on time. Christelle will have positioned herself as offering a best-case scenario while gaining leverage over those who do not wish to grant her five or seven people.

Stakeholders willing to provide the resources for an on-time project may pressure those who want to keep the additional headcount at two. That becomes a point of outside leverage for Christelle: Stakeholders for the higher headcount pressuring those against it.

Phase 2. Suppose Christelle gained buy-in for five or seven people. In that case, she will still need to protect herself at the seven-headcount level by managing project creep. Throughout the project timeline, Christelle can use leverage by calling on stakeholders who want to ensure the project's on-time delivery to sway the individuals seeking project expansions away from those efforts.

If, however, stakeholders only allotted two people to Christelle, she can chart the project's progress on a timeframe that will highlight the need for additional resources before the situation becomes dire. As soon as the ill-fated direction of the project occurs, leverage would bear a sense of urgency to correct the project's path (that is to say, "Give me more resources as soon as possible or the project may stray into deeper troubles.").

Christelle's scenario demonstrates the advantage of positioning objectives dressed as benefits for stakeholders, team members, or peers. Regardless of what people say aloud about the team being first, everyone has their self-interests at heart. Thus, the result of Christelle delivering objectives as benefits is that their beneficiaries will become more likely to embrace them, leading to a higher probability of success in each phase.

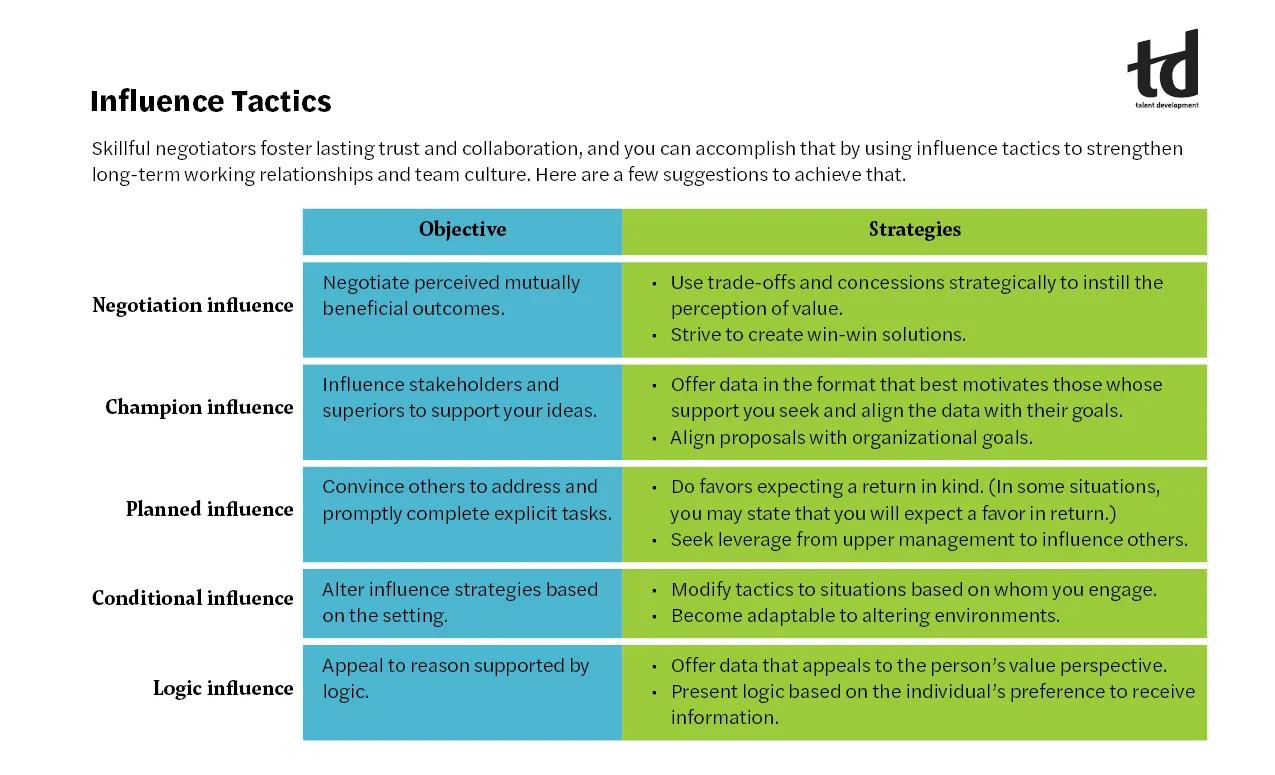

Develop negotiation strategies

Every negotiation involves different negotiator types based on the people negotiating, which means there is not a one-size-fits-all strategy to use.

Hard negotiators can seek complex deals, while easier negotiators may compromise faster. Either style can become more difficult to engage if you use the wrong strategy. Therefore, you must know the negotiator type you are dealing with, the source of their power, what they may do when you approach them with a proposal (such as be less open to compromise or serve as a partner toward a common outcome), and who is not at the bargaining table who may maneuver them.

Hard negotiator types. With hard bargainers, focus on building trust before addressing substantive issues. Look for common ground and keep interactions positive. Be mindful of the amount of control you concede. If you concede too quickly during your talks, you may be positioning yourself for the hard bargainer to request more concessions.

Despite how you concede, create the impression that the individual earned what you conceded. That will offset the perception that you are easy to manipulate and maneuver.

Easy negotiator types. To avoid rushing to unsatisfactory compromises, offer these individuals multiple options. Confirm they feel heard while you stealthily move toward optimal solutions. Allow easy negotiator types to sense they control the negotiation's flow, which will enable them to foster more trust in you and in the negotiation process.

Regardless of the negotiator type with which you're contending, prepare contingency plans or countermeasures for potential roadblocks stakeholders may raise. With proactive strategies in position, you and your team can quickly pivot when challenges arise before and during negotiations.

Uncover biases

Some people negotiate and never consider the impact that biases will have throughout the process. To uncover your biases, begin by assessing your feelings and thoughts about those with whom you negotiate—for example, stakeholders, team members, and management. Ask yourself whether you harbor animosity toward them. Why do you possess such feelings? What sources motivate you? How might your emotional state of mind during such interactions affect the individual and influence your discussions? Probe deeply to determine why you may treat them in one manner and other people differently.

The deeper the probe, the more you will discover what motivates your actions during negotiation. Having that awareness can assist you in being better prepared mentally to engage in a give-and-take endeavor with others. For example, if you are aware of triggers that will evoke unwanted behavior in yourself (for example, someone saying a particular phrase or word combination, exhibiting a certain body language gesture, or using a tone of voice that may spark negative emotions), you can mentally prepare responses (such as staying calm) before an engagement. Then, if someone with whom you're negotiating triggers you in a live environment, you'll be prepared rather than allow your amygdala (the part of the brain that activates a fight-or-flight response) to hijack your actions.

To uncover people's possible biases, use the same thought process. You may have to initially make assumptions about an individual's biases if you are unfamiliar with the person. Create a foundational baseline to assess their biases by comparing their actions to what is customary in the environment.

For instance, if an individual hails from a work environment that tends to be congenial, you should not initially assume the person is timid or lacks competitiveness if they do not display the same enthusiastic attitude about activities as their counterparts. Instead, consider other influencers.

Suppose someone has a higher educational degree—or believes they do—than their counterparts, and they flaunt that fact. You could ask them whether they are aware of what they're doing. If the response is yes, the next question could be: "Why are you making such displays?" Answer: "In my culture, we value education, and my counterparts lack it; I'm trying to inspire them to seek more knowledge." At that point, you will have exposed that individual's bias and, from there, adopt the appropriate action as determined by the outcome you seek (such as asking them not to use that method to inspire associates and inviting the individual to lead a greater effort).

If the individual says they were unaware of their actions, that may reveal an unconscious bias. Having insight into someone's unconscious bias could shift your mental perspective to become more understanding of a person's actions, leading you to adapt their manner of negotiation.

Under either scenario, you will learn about the person's bias. Having insight into your biases and the biases of those with whom you interact will enable you to grasp someone's motivating sources as well as your own.

Common TD negotiations

Managing resources and maintaining control over project scope are among the types of negotiations in which you may be involved. Those matters are important because the misappropriation of resources and scope creep can disrupt initiatives and place operations in peril.

Budgets. When creating a budget for resources, negotiate with those involved based on what they need and want as well as the minimum they require to produce the results aligned with organizational, departmental, and team goals. Ask people providing input to be realistic about those aspects. Be mindful of individuals who inflate estimates in their proposals.

In addition, assess allocations made in prior endeavors, the outcomes, and what you could have done to improve or avert situations that occurred. That will give you a baseline of how well you previously budgeted for resources, the challenges that you confronted, and how to enhance the current situation. Using historical information can help guide your negotiation efforts to successful outcomes while avoiding the pitfalls that may otherwise occur.

Having slack or padding in your budget proposal is not necessarily bad; some people use it to hedge against nonforecasted occurrences. Thus, slack may become your contingency, but be mindful of the degree of slack others include.

Be prepared to defend slack in your budget when you present to stakeholders. Also set boundaries based on how stakeholders may use your budget excess.

Project scope and creep. With the budget in hand, when dealing with stakeholders and others competing for the use or involvement of your resources, lock down every request for resources by stress-testing allocation. For example, if stakeholders asked you to reallocate or redeploy resources for another project purpose, assuming they were involved in the budget process, have them align their request to what everyone agreed to in the budget. That is also the time to become mindful of budget boundaries.

You can harm operations by doing favors outside the budget. Thus, by keeping requests aligned with budgetary allocations, you can maintain greater control over projects while avoiding project creep, which can destroy opportunities to perform better and produce more significant results for your team and the company.

Deal-making

Negotiation capabilities can make or break project outcomes and professional partnerships. You must identify stakeholder priorities, set strategy, secure resources, manage expectations, and build trust through win-win negotiation.

Mastering those practices will enable you to thrive amid complex demands and evolving priorities. With insightful preparation, a collaborative mindset, and the ability to prioritize, you can navigate negotiations more effortlessly.

More from ATD