TD Magazine Article

The Accountability Advantage

Managers who foster accountability create an environment of trust.

Mon Dec 02 2019

"Do it or else!” That’s perhaps how most leaders have experienced accountability from a supervisor—or felt about it from the perspective of trying to get a team to finish work under a deadline. Certainly, getting things done within a specific timeframe is an important aspect of being accountable. But is that all accountability is—productivity and deadlines?

The simple answer is no. To understand what accountability really is, though, we need to unwrap some major misperceptions.

Consider this scenario: A manager threatens her staff with consequences if they slip on an upcoming deadline. Granted, directives outlining what’s expected (and by when) are perfectly reasonable to ensure compliance with stated targets, as well as an important aspect of how teams can remain productive. But imagine from a worker’s perspective if that’s all a manager ever did—give tasks and deadlines about work employees must complete. If continued over time, this approach will affect both worker engagement and an organization’s long-term viability. That’s because task-based work typically doesn’t involve the creation of anything new or any efforts focused on long-term innovation.

Yes, the work got done, but the company is now in worse shape than when it started. That’s not accountability; it’s negligence. Not surprising, employees soon hate their jobs and the managers, and the company flounders from a lack of innovation.

The FACES of accountability

The Association for Talent Development has defined a new model for accountability: the FACES Framework, which entails focus, apprenticeship, challenge, education, and safety. It can enable managers to focus on helping their teams improve and succeed in the long term while getting workers to buy into their own long-term contributions and grow themselves and the company. Let’s take a closer look at each facet.

Focus

Do employees know why they do what they do? It’s great to get work done on time as a group, but it’s not going to mean anything to employees unless leaders can connect it to the organization’s broader vision and mission.

Employees want to know where they fit and what role they play. Part of accomplishing that is an onboarding program that helps new employees understand what the company does, provides organizational history and structure, and explains the employees’ role in that structure. According to a Partners in Leadership accountability study, 93 percent of employees don’t understand what their companies are trying to accomplish. Even worse, only 15 percent of businesses have true cascaded goals. That’s lack of focus right there.

Managers’ key responsibility in helping teams become more accountable is setting the vision for the group. Where does the team need to go? What must happen now to position the group for future success, not just this year but in the coming years? Leaders must put in processes for group success and communicate that their approach will focus on helping employees succeed through feedback and other means. Employees need to know that up front.

For example, during onboarding, managers should communicate that, first and foremost, their job is to help the employee succeed. With that in mind, they should structure feedback so that it comes after key performance points throughout the year and on progress toward key goals—almost like a postmortem of a new project launch. Opening questions would look like: What has gone well? What hasn’t gone so well? What would you improve? Then, the manager could ask the employee, “Would you like to hear my feedback?” In other words, managers must use simple questions that can help position themselves as helpful.

Apprenticeship

When an employee can watch someone with more tenure do something—handle a situation, carry themselves, or even simply organize something—the experience can be invaluable. Apprenticeships help employees learn their craft in a way that can’t be replicated.

Thus, managers should make time or create opportunities to model practices or behaviors for employees to give them insights. But if supervisors truly believe in developing their employees, they need to bring back an apprenticeship mindset, which they can integrate into everyday aspects of interactions.

Challenge

Let’s split up challenge into two parts. First, there is the importance of collapsing time. A vital quality that great leaders demonstrate is that they will challenge employees to not only be productive today but also set achievable goals—and then help them reach those goals—for the coming years. One way to do that is to emphasize the importance of collapsing time.

Take, for example, Thomas Keller, chef and founder of two Michelin three-star restaurants, The French Laundry and Per Se. He says that early in his career, where he started as a dishwasher, he did as much as he could to finish the dishes efficiently so he could spend more time watching the chef de cuisine’s techniques. Put another way, Keller was collapsing time and then spending it on efforts that would help his later career.

The parallel to business shouldn’t go unnoticed. By helping employees focus on collapsing time (getting the work done that they need to do today but knowing what they want to achieve tomorrow), managers can help them prioritize the importance of developing future ideas—something critical because businesses are in a constant state of change and need to continuously innovate.

The other aspect of how leaders can challenge employees comes from a concept called achievable challenge, which is the idea that a manager stretches but doesn’t overwhelm employees. Think about it from the perspective of a video game. All players start at level 1. Those who demonstrate more dexterity move quickly to the next level and the one after that, with each getting successively harder until players reach their ultimate level. Video games are addictive because they challenge players with something new at each level that is just a little harder than the last but still within reach. Similarly, in organizations, it’s important for leaders to set challenges appropriately—ones that stretch employees but don’t encourage them to give up because it’s too far beyond their own capabilities.

Education

Common wisdom holds that learning environments are essential to successful companies, but the explanation as to why that’s true isn’t always evident. Here’s how it works: The more knowledge a person has about anything, the more he is able to connect with others. The more individuals can connect, the more effective they will be at communicating. Finally, the more effective people are at communicating, the more successful they will be at accomplishing important work.

As an example, ATD mandates a learning goal for every employee and allows the time for employees to pursue the goal. The goal doesn’t have to be directly related to the work they do. Rather, ATD seeks to create a learning environment where people can apply knowledge across disciplines.

Consider the statement from Steve Jobs in 2011 when talking about the iPhone and other Apple inventions: “Technology alone is not enough. It’s technology married with the liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our hearts sing.”

The difference today between an iPhone and a Blackberry is that one still exists. The Blackberry functionally did everything the iPhone could do, but Apple employed little things learned from the arts, humanities, and design to make something lasting.

Safety

Safety is more than being safe from physical threats—sexual harassment or physical harm, for example. It’s also about psychological safety and unwittingly creating a hostile environment. Here are a few areas to keep in mind.

Hostile environment. Does a supervisor take credit when employees do good things? Good managers never need to point out how good they are. If they do, it’s an environment where employees won’t want to stay.

Part of being a good leader and teaching accountability is for managers to take the blame when things go bad and give the credit when things go well.

Early communication. Managers should not surprise their staff with last-minute announcements that affect the team. Telegraphing information is so important, particularly preparing employees for any upcoming changes. Not communicating matters far in advance can come as a shock to employees and creates an unsafe environment.

Risk. An essential part of safety is—and maybe ironically—creating an environment to take risks. Giving employees the room to try something and have that initiative not work out is as important as taking the initial risk. Creating an environment where employees are afraid to do something new will ultimately stifle their creativity and shackle a company in terms of innovation.

A window into building trust

Now that we’ve covered accountability, next is communication and building trust. Research reveals why both are important in the workplace:

The Conference Board reports that 53 percent of Americans are currently unhappy at work.

According to Gallup, managers account for at least 70 percent of the variance in employee engagement scores.

A Harvard Business Review survey reveals that 58 percent of people say they trust strangers more than their own boss.

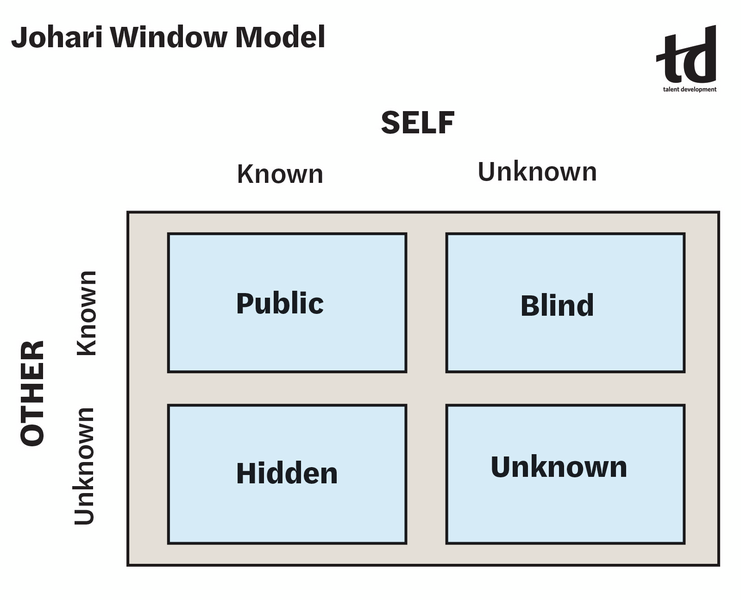

Two of these panes represent self and two represent the part unknown to self but known to others. The information transfers from one pane to the other as the result of mutual trust, which a person can achieve via socializing and receiving feedback from others.

Open or public area. This pane comprises the information about you—attitudes, behavior, emotions, feelings, skills, and views—that you and others know. This is mainly the area where all communication occurs. The larger the area becomes, the more effectual and dynamic the relationship will be. Feedback occurs by understanding and listening to the feedback from another person. Doing so increases the open area horizontally, decreasing the blind spot. You can also increase this area downward by revealing your feelings to another person, thus reducing the hidden and unknown areas.

Blind self or blind spot. This refers to information about you that others in a group know but you are unaware of. Others may interpret you differently than you expect. Reduce the blind spot via efficient communication, seeking feedback from others.

Hidden area or façade. This pane focuses on information that you know but others don’t, such as any personal information you are reluctant to reveal. This includes feelings, past experiences, fears, and secrets that you keep private. Reduce the hidden area by moving the information to the open areas.

Unknown area. Here, both you and others are unaware of certain information. This can include feelings, capabilities, and talents that are the result of traumatic past experiences or events, for example. You may be unaware of this information until you discover your hidden qualities and capabilities through observing others. Open communication is an effective way to decrease the unknown area and improve communication and trust with others.

The Johari Window Model’s goal is to provide guidance toward the act of disclosure. Expanding the size of the public pane is a key predictor of effective team functioning because it establishes trust. Healthy relationships develop at points of exposure and where communication and understanding move both ways. In other words, when a manager learns she has a blind spot about a specific project, she can communicate more clearly and earn her team’s trust. Likewise, she needs to acknowledge her team members’ blind spots to pinpoint and prepare for potential areas of misunderstanding from their perspectives. Both parties need to engage in active exposure and feedback to build trust.

Building a culture of accountability, trust, and communication is hard work—and perhaps unnatural for some. But regardless of the effort it takes, creating a culture of shared accountability and communication pays off. It’s a mindset. Managers who care about their employees care about making them better. In turn, employees get better at what they do, stay engaged, and help power the results today and for the future.

The FACES Framework

Focus

Employees want to know where they fit and what role they play. Managers’ key responsibility: Help teams become more accountable by setting the vision for the group.

Apprenticeship

Employees want to learn from experienced advisers. Managers’ key responsibility: Integrate an apprenticeship mindset and opportunities into everyday interactions.

Challenge

Employees want to gain experience through achievable challenges. Managers’ key responsibility: Set appropriate challenges that stretch employees but don’t encourage them to give up.

Education

Employees want to learn the necessary skills to perform their jobs. Managers’ key responsibility: Create a learning culture where people can apply knowledge—even across disciplines.

Safety

Employees want to know they are safe not only from physical threats but also psychological dangers. Managers’ key responsibility: Establish a working environment that’s free from hostility and safe for employees to take risks.

You've Reached ATD Member-only Content

Become an ATD member to continue

Already a member?Sign In