TD Magazine Article

The Intentional Decision Maker

Your approach to making decisions is crucial to building a more inclusive, agile, and high-performing organization.

Thu Feb 01 2024

Your approach to making decisions is crucial to building a more inclusive, agile, and high-performing organization.

People make tens of thousands of decisions per day—in fact, a Cornell University study found that up to 300 of those are about food alone. To stay functional and keep moving through life, individuals make most daily decisions automatically, without thinking too much about them.

But when people come together in a business context to make decisions, the process often becomes sticky and dysfunctional. Such dysfunction may take the form of teams stuck in an endless loop, trying to achieve perfect consensus. It may look like over-relying on structural authority (such as rank, title, or tenure) as a proxy for decision-making capability when determining who should lead those activities. Back-channeling, forgetfulness, urgency, miscommunication—there are myriad ways a decision-making process can get stuck, lost, or headed in the wrong direction.

Organizations and teams can't rely on the same default decision-making habits that make individuals more efficient and effective. Doing so only reinforces structural inequities and dysfunction, even if a company is vocally committed to collective transformation (in other words, big ideas such as innovation, trust, agility, and empowerment).

But if you, your team, and your company adopt a more intentional decision-making methodology, you can change how those big ideas manifest within everyday moments throughout the organization. Change how you make decisions, and you'll change the company culture.

The impact of decision making

Research from Bain & Company reveals that companies that excel at decision making "generated average total shareholder returns nearly six percentage points higher than those of other firms," according to the Harvard Business Review article "The Decision-Driven Organization." Six percent can equate to millions or billions of dollars.

Further, a Cloverpop study notes that teams that follow an inclusive process make decisions two times faster, with half the meetings, and the decisions diverse teams make and execute deliver 60 percent better results.

Clearly, decision making can be a powerful lever for building a more inclusive, agile, high-performing organization.

Drawbacks of RACI charts

Inevitably, when I talk about decision making with clients, one of the first questions that comes up is: "What about RACI?"

After eight years of consulting with hundreds of large, complex organizations that use the RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, informed) model in their decision making, my colleagues at consulting firm August Public and I have concluded that a RACI chart, which is a type of responsibility assignment matrix, is not a useful decision-making tool. We have found that it lends the illusion of clarity and efficiency to decision making, and it instead serves to document existing organizational dysfunction.

Our experience is that a RACI chart rarely moves decision-making authority to the right level. A team typically creates a chart once for a project without accounting for the dozens or hundreds of decisions that will drive that project forward. Further, the chart gives no guidance for how decision making will occur; it's only a template for whom to blame when things go wrong.

A more effective decision-making method is to designate an empowered decision owner, supported by a robust stakeholder map.

Empowered decision ownership

A decision owner is the person who makes final decisions even if others (even those more senior) disagree. The individual should have expertise in the decision at hand, reliable access to data to make an informed choice, time for the process, and the skill to solicit and integrate diverse perspectives.

The ideal decision owner is usually not at the top of the organizational chart, and they work in close contact with the people who will be most affected by the decision. The decision owner must have a nuanced perspective on how large-scale decisions from the top translate into outcomes on the ground and be best positioned to spot unintended consequences and risks before they balloon.

One example demonstrating the benefit of distributing decision ownership away from the top leader is the story of how Netflix CEO Reed Hastings initially passed on the pilot script for the TV show Stranger Things. In his opinion, it didn't seem like a runaway global hit. Fortunately for the streaming service, Hastings wasn't the only one with decision-making power. A manager several rungs lower on the organizational chart greenlit the pilot after Hastings declined, thereby launching one of the biggest hits in streaming history and delivering outstanding results for the company's bottom line.

Hastings's near-miss is a stark illustration of how critical it is to have the right person—instead of defaulting to the highest-ranking person—at the helm of each decision.

I saw distributed decision ownership in effect in 2022, when August Public consulted with a software company on its transition to a hybrid workplace. While other large organizations mandated a return to the office, driven by leadership agendas and preferences, the software company empowered managers to make the call for their respective teams.

Within the guardrails of the software company's hybrid-centric initiative called Flex Forward, each manager can now decide when—or whether—their employees come into the office. That shift recognizes that managers are best equipped not only with expertise, time, and data, but with the skill to incorporate diverse perspectives into an inclusive and empowering plan for their teams.

The support system

To be inclusive, many organizations default to a consensus model of decision making. However, in practice, consensus isn't inclusive. Mandatory agreement silences relevant and dissenting perspectives because people will self-censor just to keep the process moving.

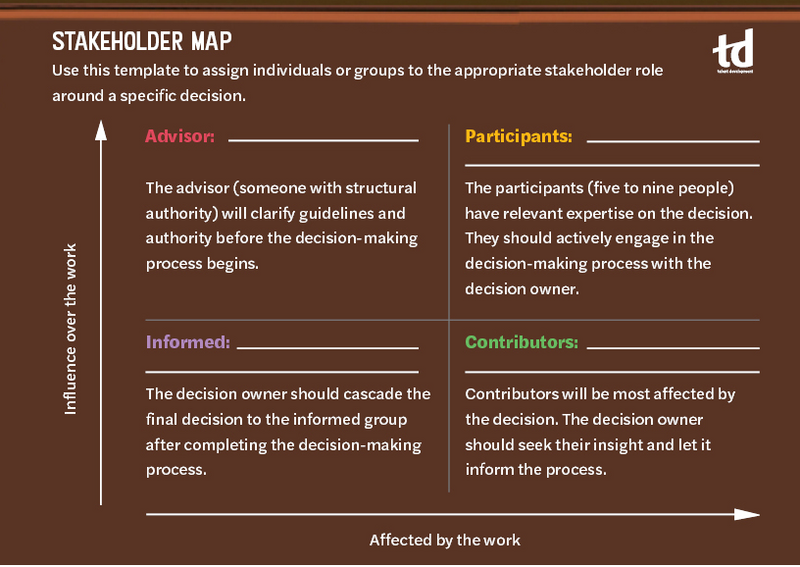

A stakeholder map, on the other hand, is a method for building meaningful inclusion without requiring unanimous agreement. It is a way to deliberately choose whose voices should influence the decision owner's process as well as a means of finding creative ways for soliciting input and insight from the wider community. The map consists of four groups: advisors, participants, contributors, and informed stakeholders (see figure).

Within the Flex Forward program, advisors were mainly the company's C-suite leaders (the CEO, chief HR officer, chief media officer, and chief technology officer), who each provided insight on the resources and limitations for taking the company hybrid. Participants were key leaders from affected areas (facilities, finance, and sales). Contributors were all employees; their managers surfaced and represented their opinions and preferences. Informed people were those who already worked remotely as well as certain other groups (contractors, service organizations, and the general public who followed the story).

The emergency brake

Because so many people conflate inclusion with the slow grind of consensus, there's a big misconception that inclusive decision making will slow things down. The distinction, however, is that consensus slows down a process, while inclusive decision making speeds things up.

The decision owner and stakeholder map model are built on a bias toward action: With one person tasked with making the final decision, universal agreement is not a prerequisite for moving forward. In place of consensus, stakeholders have an emergency brake to keep the organization safe from the fallout of a faulty decision. That fail-safe tool is called safe to try.

After the decision owner has integrated the perspectives of the stakeholder map and proposed a final decision to the participants, the decision owner will ask, "Is this decision safe to try?" The participants must say yes—unless someone voices a valid objection that proves the decision is not safe to try. A valid objection is not:

A gut feeling or vague concern

A preference for a different decision

A concern about the decision's failure to address other unrelated problems

Those objections can be important considerations, but they don't make a decision unsafe to try.

A valid objection provides hard data that the decision will cause immediate and irreparable harm, such as:

Badly undermining another team's project

Damaging a critical relationship

Repeating a mistake the team has made in the past

When participants raise those types of objections, the decision owner then works with them to adapt the decision in a way that will make it safe to try.

The safe-to-try approach frees everyone to voice their concerns while keeping the process moving forward. That makes it possible to make inclusive decisions quickly, with minimal risk. In addition, the approach shifts the decision goal toward learning and discovery, which empowers faster decisions and quicker adoption of successful strategies. That in turn leads to better business outcomes on a shorter timetable, all while building inclusion and empowerment. Proceeding and learning become the default option so that individuals try new ideas and learn from them.

Capture and communicate

How many times have you found yourself experiencing decision déjà vu in a meeting? You know your team already made a decision about the topic at hand, but no one can remember what it was.

To avoid such a scenario, after the decision owner makes a decision, it's essential to communicate it widely and clearly. Skipping that step will result in revisiting the same decision down the line.

The key role in decision capture is the scribe, a rotating role fulfilled by one of the participants. Every time a decision maker comes to a decision, the scribe writes it down in an open, shared digital document. The file should include the decision method, the stakeholders, the rationale and context that influenced the decision, in addition to the decision's anticipated impact and trade-offs. The scribe next circulates the decision to everyone on the stakeholder map.

The final decision-making step is to set a schedule for implementing, evaluating, and recalibrating, if necessary, to maximize the learning value of the decision as well as get the best return on the time and energy invested in the decision-making process.

Rethink decision making

The outlined methods are built on three fundamental mindset shifts:

A shift from implicit authority to explicit authority will enable you and your team to practice empowered decision ownership, resulting in better outcomes and faster processes as well as galvanizing more diverse voices to have a tangible impact.

A shift from "Is it right?" to "Is it safe to try?" will free your organization from perfectionism, making space for dissenting perspectives and enabling the team to learn faster by defaulting to action.

A shift from decision secrecy to decision visibility will maximize the learning value of the decision and minimize any inefficiencies or miscommunications in its wake.

Those shifts have the power to bring an organization's biggest ideas into the daily reality of its workforce. A business shifting its decision-making process from default habits to intentional practices that align with company values will drive culture change faster than ever before. Redesign how you, your team, and your company make decisions, and you'll change the entire organization from the inside out.

You've Reached ATD Member-only Content

Become an ATD member to continue

Already a member?Sign In