TD Magazine Article

True or False: Your Test Questions Could Use Some Improvement

How you word and structure learner assessment questions can make the difference in whether you capture reliable, meaningful data.

Thu Dec 30 2021

Bookmark

To this day, it is likely I am the only student in Southern Illinois University history to take the same class four times. (For those of you thinking that may not be the best statement to instill confidence that I can help you write better assessment questions, please stay with me here.)

At that time, I was a broadcasting student taking a required broadcast law class that would reveal itself to be the most challenging class in my 10 years of collegiate studies. I took the class once but dropped it due to poor performance. I took it again, earning an F instead of a withdrawal. I took the class yet again, finally achieving a D, which was considered passing.

Prior to my third attempt, the professor called me to his office and told me that he knew I knew the material, but he couldn't understand why I could not pass his tests. I did not have an answer. I knew that, even after my initial half semester of his class, students who had earned an A observed that I could apply broadcast law concepts better than they could.

It did not dawn on me that the test itself may be the problem until, in pursuing my second bachelor's degree, I enrolled in a special topics class focused on teaching and learning. In that class, I was introduced to Sharon Shrock and William Coscarelli's book Criterion-Referenced Test Development, which was foundational in building my understanding that there are right and wrong ways to assess learning.

Death by matching

Using that knowledge, and with the broadcast law professor's permission, I audited his class, which was the only way by university policy I would be allowed to take the class a fourth time. I looked at anything that pointed in a different direction from what Shrock and Coscarelli explain, but I found nothing. My conclusion was that it was the nature of the tests themselves that contributed toward so many students failing the class each semester.

One hundred percent of the class grade derived from three tests, each of which entailed what I colloquially call "death by matching." Matching tests can create anxiety in test takers even when they consist of small groupings of five terms in one column and five phrases in another column. Ours comprised 50 court cases in the left column, numbered 1 through 50, and 52 phrases in the right column, lettered A through ZZ. Each phrase in the right column listed outcomes of court cases that were similar to the others but ever so slightly different in nuanced ways. The professor essentially was testing us on how well we recalled the nuances as opposed to how well we understood the general concepts or, more importantly, how well we could apply the rulings in a corporate broadcast environment.

What's best for the six levels of cognitive learning

Matching tests are inadequate because they can only be effectively used to test recall. They cannot be used to test the higher Bloom's taxonomy levels of apply, analyze, evaluate, and create.

Which testing approach best measures the higher Bloom's taxonomy levels? Arguably, only essay questions offer the flexibility to test across all six levels—remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create. Short-answer questions provide nearly the same flexibility but fall short of testing the top levels of evaluate and create. Both styles benefit from allowing open-ended questions that are easy to construct but must be graded manually.

The more essay questions there are to grade, the less reliable the scoring becomes, because results can differ due to scoring sequence, scorer fatigue, and halo effects if the essays are not somehow anonymized. Also, much like matching questions, essay questions can cause testing anxieties among many participants.

This is where the oft-maligned multiple-choice (and multiple-selection) test question can be seen in a positive light. Test creators can word multiple-choice questions in ways that effectively test the first four levels of Bloom's taxonomy, much like short-answer questions. However, unlike short-answer questions, multiple-choice questions are easy (and fast) to grade electronically or by hand while remaining the most flexible of the closed-ended question types.

So why do multiple-choice questions get a bad rap? The speed and ease of grading are offset by the extra energy and effort needed to craft questions in such a way that test takers cannot easily guess them, that the questions do not create unnecessary test anxiety, and they do not inadvertently test an individual's ability to take the test.

The ability to reverse engineer test questions is something I also tested during my undergraduate studies. For two classes, whose grades were solely derived from the results of multiple-choice tests, I made the unfortunate and ill-guided decision to use the information in Criterion-Referenced Test Development to make educated guesses through my midterm and final exams. While I did not earn an A in either class, I likewise didn't earn a D or F.

Since that time, I have only used these superpowers for good. To that end, I would like to share some of the methods crafty students often use to reverse engineer multiple-choice assessment questions and how test creators can mitigate against them.

Guessing game

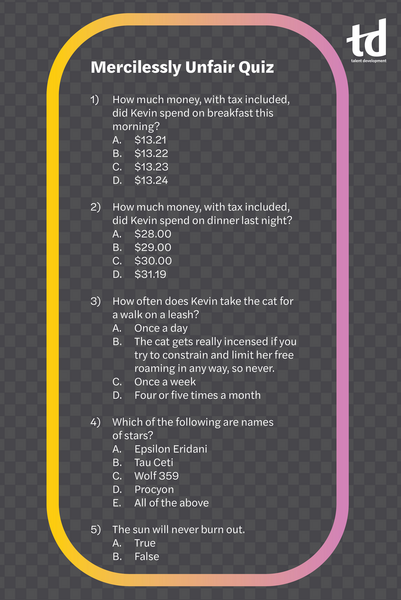

When I present on this subject at conferences, I like to have participants take my "mercilessly unfair quiz." It features questions for which participants could not possibly know the answer, yet most manage to score 80 percent or higher. Let's look at each question and answers in greater detail.

Question 1 provides a list of responses that only vary by three cents. There is no way to know the answer, which results in only one option: to guess. When I ask the question during a presentation, more than half the room will select answer C, though few will be able to explain why they answered the way they did.

C is indeed the correct answer. That parallels the thought process we follow when we build our own questions and answers. We usually reserve A for our best distracter and would rarely put the correct answer toward the top. What, after all, would happen if a test taker read answer A and knew it was the correct answer without reading the other painstakingly created incorrect answers? (They would pass the question, but in drafting the possible responses, that is not how we often think.)

Answer B is usually, though not always, a slightly different wording of answer A. We often are reluctant to place the correct answer as D for similar reasons why we avoid A: What if the learner reads through all the possible answers and, not knowing which to choose, selects the last in the list? D, then, often becomes a distracter—and because we often use our best distracters earlier in the list, D frequently becomes the weakest distracter. Sometimes we make it even weaker by making D a funny answer (for example, "Kevin is a dine-and-dasher so he paid nothing for breakfast"). While humorous distracters can relieve test anxiety, they become a throwaway because they no longer distract, making it easier for learners to guess the correct answer and also creating risk that learners will not take the assessment seriously.

If we are not careful and conscious of the correct answer's placement among the distracters, we tend to place the correct answer most often as C and second most often as B. Fortunately, some authoring software provides the ability to scramble the order of answers in multiple-choice questions. If your authoring software lacks that capability, consider listing answers in a logical order (either alphabetically or chronologically) to minimize that effect.

The standouts

Question 2 is similar to Question 1, though the answers reveal a key difference: All except one of the answers are approximations, or rounded off. The one answer that provides an exact dollar amount tends to stand out. When a test taker has no idea what the answer could possibly be, they will frequently focus on any answer that stands out, and it is that extra focus or second glance that will often cause them to select that answer as their guess. The correct answer is D.

Such differences can appear in other ways. Sometimes an inadvertent extra space will grab a test taker's attention, or it may be a typographical error or a slight mismatch in font type or size. Any of those factors will cause that extra glance, which will—rightly or wrongly—often prompt a learner to select that answer. To avoid that, always proofread for consistency, and consider using all general or all specific answers without mixing and matching.

Imbalanced responses

Question 3 has multiple issues. Most people will be drawn immediately to the longest answer. We tend to put more effort into the correct answer's wording than we put into the distracters. We also often consider assessments not as an event that comes after the formal learning process but rather as part of it. As a result, we often attempt to pack more information into the correct answers as a teachable moment. Test takers can pick up on that. Most will select answer B, which is the correct answer, solely on that principle.

However, recall what I mentioned earlier about using humorous answer choices. In this instance, the humorous choice is the correct answer rather than a distracter. Any answer choice that draws extra attention can result in a lack of balance and may ultimately reduce the validity of the assessment. Similarly, validity is negatively affected when two or more distracters, worded differently, are essentially the same answer, as seen in answer choices C (once a week) and D (four or five times a month). Even if B did not stand out as the correct answer, easily dismissing answers C and D converts this question into a 50/50 coin flip.

The key takeaways with Question 3 are to keep the answers similar in length as much as possible, ensure your answer choices are equally believable but not identical in meaning, and avoid humorous answer choices regardless of whether they are distracters or correct answers.

All of the above

Question 4 offers answer choices that many astronomy and sci-fi fans could probably answer. But there is one thing that keeps everyone else from reaching for their smartphones and searching the answer choices: "All of the above." We tend to use that response infrequently in tests to the extent that when it appears, learners' attention is drawn directly to it. It is not uncommon to experience an assessment in which every appearance of "All of the above" is the correct answer. That, as well as the further observation that there's a fifth answer choice for this question, causes most respondents to correctly identify the right answer as E.

In general, it is best to avoid using "All of the above" as an answer choice. Once a test taker identifies two of the answer choices as being correct, they will not consider the remaining answer choices, making the question ineffective. To get around that, consider using a multiple-selection question, prompting learners to select any, all, or none of the answers as correct.

In the rare instance that "All of the above" is unavoidable, consider using it for all questions within a single assessment. It is also best to avoid using "None of the above" as an answer choice, as well as confusing answers such as "Only A, B, E, and G."

Coin toss

Question 5 is technically a multiple-choice question, even though there are only two choices. This 50/50 coin toss gains greater odds of having its correct answer guessed by use of the word never. True-false questions using always and never are usually false because both words establish an absolute condition. Most things in life are less like a light switch and are more like a dimmer switch, so rarely will a situation exist where always or never applies. The correct answer is B.

While true-false questions are great for use as ungraded knowledge check questions, they rarely have a place in graded assessments, particularly because it is difficult to create a true-false question reaching higher than the remember level on Bloom's taxonomy. That said, there are rare instances where only two plausible answers exist—in which case it may be more effective to create a two-answer multiple-choice question than a true-false question.

Avoid the pitfalls

This article provides a few observations and recommendations that hopefully will guide you in creating assessment questions that truly measure what you want to measure. Looking back, some of the examples may appear overly simple, but they illustrate common pitfalls we often experience as test takers and, if we aren't careful, as test builders as well.

The Most Common Test Question Types

True-False

Easy to write and easy to score

Easy to guess

Best used to measure the remember level on Bloom's taxonomy

Matching

Easy to write and easy to score

Creates testing anxiety in some

Best used to measure the remember and understand levels on Bloom's taxonomy

Multiple choice/selection

Easy to score

More difficult to write

Can test all levels of Bloom's taxonomy except evaluate and create

Fill in the blank

Easy to write

Measures recall, not recognition

Can test the remember, understand, and apply levels of Bloom's taxonomy

Short answer

Easy to write

Measures recall, not recognition

Can test all levels of Bloom's taxonomy except evaluate and create

Essay

Measures recall, not recognition

Must be graded manually

Can be used for all levels of Bloom's taxonomy

Additional Test-Writing Tips and Tricks

Nearly all question types can create test anxiety, so variety is good; mix up the question types.

Highlight negative words such as no, not, and none.

Only use negative words when they are essential.

Preface multiple-choice questions with "Choose the best answer."

Alert test takers to multiple-selection questions (for example, "There may be more than one answer" or "Choose all the answers that apply").

Make instructions clear and thorough yet succinct.

Keep point totals evenly divisible into percentages: divisible by 10 for a 90 percent passing rate; divisible by five for an 80 percent passing rate; and divisible by four for a 75 percent passing rate.

More from ATD