The Public Manager Magazine Article

Solving the Dilemma of Senior Executive Training

An inside look at a leadership development program in the federal sector sheds light on how best to prepare senior executives working in government.

Tue Mar 03 2015

Bookmark

The Fall 2012 issue of The Public Manager included the article, "Building an Architecture for Leadership Development," which detailed the underlying framework for agency-wide leadership development programs in federal-sector agencies. Three years into the successful execution of this vision at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), it is time to share our lessons learned and best practices for developing leadership skills among one of government's more challenging populations: senior executives.

The Dilemma

On any given day, senior executives in the federal sphere face daunting challenges that require well-honed leadership skills. This past fiscal year serves as a clear example; from the government shutdown, sequestration, fiscal constraints, and loss of over 40,000 federal positions, to increased uncertainty following the mid-term elections.

It should come as no surprise that getting senior leaders to concentrate on developing sound leadership skills is problematic. Indeed, executives face a daily dilemma: Where should they focus their attention? On strategy? On operations? On employee morale?

Sound advice from the Harvard Business Review article, "Leadership in a Permanent Crisis," suggests that "individual leaders just don't have the personal capacity to sense and make sense of all the change swirling around them ... you must use leadership to generate more leadership deep in the organization."

But before senior executives can foster leadership in others, they need to be adept at leading effectively. This raises the stakes for acquiring fundamental leadership best practices that can cultivate the leadership culture necessary to sustain an organization facing a climate of permanent crisis.

Innovative Design

With this in mind, we developed a pilot series known as the "Senior Officer Seminars," which was provided as an open-enrollment option for senior executives. The seminars' design was based on established executive core competencies (ECQs) from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), including leading change, leading people, leading results, business acumen, and building coalitions.

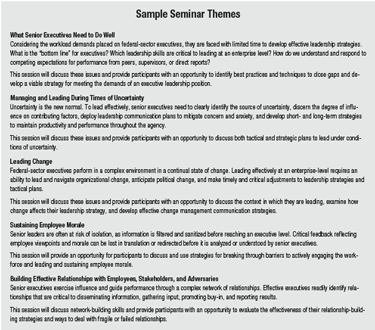

In addition, we integrated feedback from an existing competency gap analysis and employee viewpoint scores into the core themes for the program. For example, themes for year one of the pilot program included:

what senior executives need to do well

managing and leading during times of uncertainty

leading transitions

sustaining employee morale

leading culture change

building effective relationships with employees, stakeholders, and adversaries

leading at an enterprise level.

Meanwhile, more advanced themes for year two of the pilot included:

leading at an executive level

leading change and building consensus-negotiation

navigating change and obstacles

setting a vision amidst uncertainties

resilience.

Outreach Plan

To effectively promote the pilot, we developed a targeted announcement that presented all upcoming sessions, enabling senior executives to individualize their participation. The announcement was distributed through an executive listserv from the chief human capital officer.

Executives were enrolled through the learning management system, and a program coordinator stayed in touch with the participants to confirm enrollment and send reminders. In fact, the role of the program coordinator in maintaining contact with the participants was critical to sustaining a robust enrollment.

Resource Requirements

One of the advantages of the program is the limited level of resources required to conduct the seminars. The internal team consisted of a leadership development subject matter expert, a program manager, and a training technician.

The only additional resource necessary was modest funding for an external vendor to procure guest speakers and provide session materials. Participation by regional office and field staff was accomplished at no cost using a video teleconference.

Lessons Learned

Based on our experience with the first two pilot years, we noted the importance of several key elements.

Time management

Sessions were initially designed for two hours, but later adjusted to 90 minutes—based on our observations of how long it took for the Blackberries to appear. In year two, we expanded the time between sessions from four weeks to six weeks.

In year three, we plan to reduce the number of sessions that require a guest speaker. This will create additional opportunities for senior executives to share challenges and best practices with each other. These sessions will be facilitated by internal faculty and SMEs in leadership development.

Guest speaker selection and preparation

The importance of guest speaker preparation was very clear from the start. Working from a vendor-provided list, we selected speakers based on background, career experience, and evidence of best practices that could be modeled by senior executives.

Preparation included a 45-minute planning call and an announcement describing the session and key questions the speaker would cover. Materials, such as articles and handouts, were kept to a minimum. The intent of the seminar was to promote dialogue and share ideas among senior executives, rather than serve as a formal instructional activity.

Role of internal faculty

Internal faculty members were critical in setting the stage during the introductory portion of the seminar. They created the bridge between the theme or theory and the realities within the senior executives' organizations.

In our case, the dean of the College of Leadership Development served this role. She brought the added benefit of her tenure with the agency, and credibility as a subject matter expert, and established relationships with participants.

Supporting integration

To support integration of speaker comments and themes, we drafted follow-up notes. These were sent to the aggregate list of participants who had enrolled in current and past seminars. This was very well received, especially by those who were pulled from the seminar at the last minute due to urgent workplace demands.

Dynamic Design for the Future

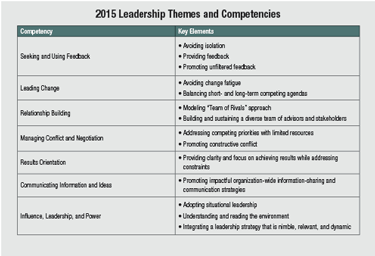

As we plan for 2015, we continue to adjust the themes and focus—based on competency gap data and Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey scores. This year, we expect to cover several additional themes. For example, for a theme of "seeks and uses feedback," key elements will include avoiding isolation, providing feedback, and using mechanisms for promoting unfiltered feedback. (See sidebar for a breakdown of competencies and key elements.)

We also are considering optional intersession executive coaching. The goal is to provide additional support for senior executives who could benefit from scheduled time to focus on specific skills and best practices identified during the seminars. In this case, a cadre of executive coaches would be briefed on session themes and best practices.

Bottom line: Based on participant feedback, the senior officer seminars have been very well received, and are considered focused, efficient, and cost effective. One participant said it best: "Excellent presenter with concrete lessons to use from day to day." That's just the sort of feedback we were striving for.

In fact, we anticipate the program will become an integral part of the organization's architecture for leadership development and serve a key role in bringing executives together for a timely dialogue on strategies and challenges.

Disclaimer: The Securities and Exchange Commission, as a matter of policy, disclaims any responsibility for any private publication or statement by its employees. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission or the author's colleagues upon the staff of the Commission.